Subject Guide

Mountain West

Malachite’s Big Hole

Ramsey Crooks:

This biography focuses primarily on Crooks early years in the fur trade especially his experience with the Overland Astorians.

Ramsey Crooks was born January 2, 1787 in the Scottish seaport town of Greenock.

His father, who was a shoemaker, died when Ramsey was in his early teens. His widowed

mother decided to emigrate to Canada along with Ramsey and one of his sisters. Previously

one, or two of his older brothers had emigrated to Canada and his mother wished to

join them. Ramsey, his sister and mother arrived in Canada early in 1803. The two

women probably settled in Niagara, but Ramsey went on to Montreal where he found

employment with a supply firm which specialized in dry goods and hardware for the

Indian trade in what was then considered to be the far west. In the spring of 1805

Ramsey quit the supply company and traveled to Michilimackinac (known today as Mackinac)

where he became a clerk in the employ of Robert Dickson & Co. In the following years

he ranged throughout the Old Northwest, Upper Mississippi Valley and as far south

as St. Louis. In those times the fur trade was based almost entirely on trade with

the Indians, not on white hunters and trappers directly exploiting the fur resources

of the wilderness. Although the Indian had no concept of land as private property,

they did recognize, and jealously guard what amounted to property rights in deer,

bear, beaver, raccoon, muskrat and other game animals which ranged their hunting

grounds.

father, who was a shoemaker, died when Ramsey was in his early teens. His widowed

mother decided to emigrate to Canada along with Ramsey and one of his sisters. Previously

one, or two of his older brothers had emigrated to Canada and his mother wished to

join them. Ramsey, his sister and mother arrived in Canada early in 1803. The two

women probably settled in Niagara, but Ramsey went on to Montreal where he found

employment with a supply firm which specialized in dry goods and hardware for the

Indian trade in what was then considered to be the far west. In the spring of 1805

Ramsey quit the supply company and traveled to Michilimackinac (known today as Mackinac)

where he became a clerk in the employ of Robert Dickson & Co. In the following years

he ranged throughout the Old Northwest, Upper Mississippi Valley and as far south

as St. Louis. In those times the fur trade was based almost entirely on trade with

the Indians, not on white hunters and trappers directly exploiting the fur resources

of the wilderness. Although the Indian had no concept of land as private property,

they did recognize, and jealously guard what amounted to property rights in deer,

bear, beaver, raccoon, muskrat and other game animals which ranged their hunting

grounds.

The geographic boundaries of the Old Northwest were left unsettled by the Peace of Paris in 1783. This treaty allowed access to the region by Canadian based British fur trading interests. Access to these regions by the British was later formalized in Jay's Treaty. Because the fur trade depended in large part on the goodwill and friendship of the Indians, a type of cold war situation developed between American and British interests for the loyalty of the Indians.

In the years leading up to the War of 1812, tensions and uncertainty in the region continued to grow. British fur interests continued to push the interpretation of the treaties to include access to the Louisiana Territory and the rich fur bearing regions it contained. This access by foreign interests greatly bothered Governor Wilkinson, then governor of Louisiana (Missouri was not yet a state). In August 1805 Governor Wilkinson issued an edict, more or less on his own authority, but with the backing of other government officials that banned citizens, and subjects of foreign powers from entering the Missouri River region for purposes of trade with the Indians. The edict also stated that all agents, patrons and interpreters were to take and subscribe an oath of fidelity to the U.S. and of abrogation to all other powers.

Early in 1805 Robert Dickson had divided trade responsibilities for his company into three geographic areas. A trusted subordinate was assigned the St. Peter's River region, Dickson took the critical Upper Mississippi River region, and the equally critical Missouri River region he assigned to James Aird. At this time Crooks was one of Aird's clerks. Aird arrived in St. Louis in September 1805, just one month after Governor Wilkinson's edict banning foreigners from trade on the Missouri River went into effect.

Although many British and Canadian traders suffered huge losses as a result being unexpectedly banned from the Missouri River, Aird was able to sidestep this problem. One of the provisions of Jay's Treaty stated that residents of the Old Northwest border area in 1796 should be considered American citizens unless they declared otherwise. Aird had been in the area in 1796 and had not declared himself a citizen of Canada or Britain. He was therefore considered to be a citizen of the United States. His boat crews were all foreigners, and would have to be replaced with U.S. citizens. Apparently his clerks, including Ramsey Crooks, fell into the category of "agents, patrons and interpreters" and were able to become Americans by taking the oath of fidelity. Thus Ramsey Crooks, perhaps without enthusiasm, became a U.S. Citizen.

Finally, sometime in October, Aird got his new crews moving west. By winter Aird's men had pushed upriver at least 600 miles, somewhere beyond the mouth of the Platte River. Because he had gotten such a late start, other traders had already gotten the bulk of the furs available for trade. Returns were poor, and by spring Aird still had large quantities of goods on hand. The clerks inventoried the goods, then cached them in the vicinity of the mouth of the South Platte. They then took what few furs they had back downriver to St. Louis. Aird would contribute little to the success of Robert Dickson & Company in this season.

In June 1806 Aird sent his meager harvest of furs back to Michilimackinac from St. Louis. Entrusted with transporting the furs to Michilimackinac and returning fresh supplies were two clerks, Ramsey Crooks and James Reed. Aird remained in St. Louis to prepare for another trip up the Missouri River. Aird planned to use the goods cached at the mouth of the Platte River to trade for summer deerskins. During this time he would also prepare a site for a winter camp amongst the Sioux Indians somewhere between the Big Sioux and James Rivers (in present day southeastern South Dakota). In the fall, Aird would return to St. Louis to guide the fresh supplies of trade goods back upriver.

When Crooks and Reed arrived at Michilimackinac, they found that Dickson had successfully renegotiated the company's debt, and that fresh supplies were available. A new name enters the picture at this time. John Jacob Astor agreed to pay the U.S. import duties on the goods, providing that Robert Dickson & Company sell him their best muskrat and martin. While here, Crooks and Reed also learned that a new monopoly and powerful new competitor, was about to be formed to operate south of the border in the United States. The Michilimackinac Company was to be capitalized at nearly the same level as the North West Company. It was apparent that Robert Dickson & Company would soon either go under, or join with the new monopoly. Meanwhile, Crooks and Reed had their hands full preparing goods and supplies worth between $12-15,000 for transport back to St. Louis and thence up the Missouri River.

On the evening of September 20, 1806, Crooks and Reed were back on the Missouri River. St. Louis was behind them, and they were preparing to tie up their boats opposite the little village of La Charette, the last outpost of civilization. At this moment, Lewis & Clark and their party appeared on the river, "like sun blackened ghosts from the Pacific." Crooks and Reed not only had the opportunity to meet Lewis & Clark, but as noted in Clark's personal journal "...those two young Scotch gentlemen furnished us with Beef, flower, and some pork for our men, and gave us an agreeable supper. as it was like to rain we accepted of a bed in one of their tents." Imagine being able to monopolize Lewis & Clark for dinner and an evening one day prior to their return to St. Louis. Presumably the talk would have turned to beaver and the fur resources of the Upper Missouri River. The explorers probably told Crooks and Reed some variation of what Lewis would write to Thomas Jefferson three days later from St. Louis: "That portion of the continent watered by the Missouri and its branches from the Cheyenne (today's central S. Dakota) upwards is richer in beaver & otter than any country on earth."

Aird rejoined his clerks on the Missouri River that fall and together they returned upriver. Not everyone would return to the the winter post Aird had prepared though. Subsidiary posts were established near various Indian villages along the river. Crooks probably spent the winter near a village of the Maha Indians, where Robert McClellen also had a trading house. By the spring of 1807 Crooks and McClellen would become partners in their own trading venture.

The new partners would find financial backing from Sylvester Labaddie and Auguste Choteau. With this backing Crooks returned to Michilimackinac to obtain trade goods and supplies. At Michilimackinac Crooks would find plenty of turmoil. Robert Dickson & Company had failed, and final accounting was only waiting on the return of James Aird from the Missouri River. Tension between American officials and British fur interests was extremely high. Indians in the Old Northwest were restless and not producing furs: Tecumseh and his brother Tenskwatawa, the Prophet, were assembling a confederation of tribes to oppose American settlers in the Ohio Valley. And finally war with Britain was looming. On June 22, 1807, the British warship Leopard fired on the American frigate Chesapeake, killing 3 crewmen and injuring 18.

Against this backdrop Crooks and McClellen set off up the Missouri River in September of 1807. They had two keelboats with a brigade of 80 voyageurs. Fortune, however, did not favor the partners. They had just passed the mouth of the Platte River when they met Nathaniel Prior and A.P. Choteau and their brigade coming downriver, accompanied by the Mandan Chief, Big White. Prior and Choteau had been hired by the government to return Big White to the Mandan villages (Big White was one of the Chiefs that had been invited by Lewis and Clark to visit Washington). This should have been a windfall for Pryor and Choteau, who intended on passing the Mandan villages on their way to trap and trade on the Upper Missouri River anyway. To get to the Mandan villages the brigade first had to pass the Arikara villages. The Mandans and the Arkikaras were then at war, and the Arikara were not about to let a Mandan Chief pass. Pryor attempted to negotiate passage, however the discussions became heated, deteriorating until gunfire was exchanged. After a fifteen minute battle, Pryor signaled a retreat, back down the river. All of this was relayed to Crooks and McClellen when the two parties met.

Crooks and McClellen decided to stay where they were at rather than risk further hostilities upriver. This change in plans left the partners overstaffed and it is unlikely they were able to collect sufficient pelts and skins to cover wages.

Finally when they returned to St Louis the following spring, they found that fur prices had plummeted. The Chesapeake incident had not led to war, however, Congress had passed the Embargo Act on December 27, 1807, which forbade American ships to clear for England or France. The Act also re-invoked the non-importation decrees of 1806 which excluded many articles of British manufacture from the U.S. The embargo did as much, if not more, economic damage to the United States as it did to Britain and France. St. Louis markets were glutted with skins and furs-prices were so low that dealers were unwilling to trade anything. Unable to dispose the skins in St. Louis, apparently Crooks transported them back to Michilimackinac. There, as an American citizen, he was able to exchange them for trade goods.

By September 16, 1808 Crooks was back in St. Louis with the trade goods he had obtained at Michilimackinac. There he met Robert McClellen. On September 30, 1808, Robert McClellen & Company was granted a trading license. The license was probably a disappointment to the partners. It limited them to 175 miles short of where they had previously traded on the river. Joseph Robidoux, and experienced trader, was deeply entrenched in this area and competition would be exceedingly fierce.

The St. Louis Missouri Fur Company was in the process of being formed at this time and it had many influential backers and partners. It is quite likely that the license received by McClellen and Crooks was calculated to minimize competition with the St. Louis Missouri Fur Company. Partners in the St. Louis Missouri Fur Company included Manuel Lisa, Reuben Lewis (brother of Governor Merriwether Lewis) and William Clark, general of the territorial militia, among others. These partners intended their control of the Upper Missouri River region to be absolute and total. Governor Lewis gave the company a $7,000 contract to deliver Big White to the Mandan villages. Governor Lewis also promised he would grant no licenses to any other traders above the Platte River and furthermore, would not allow any other party to move up the river prior to the departure of St. Louis Missouri Fur Company brigades. Although Crooks and McClellen applied and received their license before the St. Louis Missouri Fur Company formally came into existence, it seems quite probable that the government officials who would become partners in the St. Louis Missouri Fur Company were already handicapping it's competitors.

In any case, Crooks and McClellen were not overly successful in collecting furs and skins at their licensed location. On April 12, 1809 a notice was published in the St. Louis "Missouri Gazette" formally dissolving their partnership and requesting any parties with a claim against the company to come forward for settlement. Almost immediately after publication, news arrived in St. Louis that the Embargo Act had been repealed. St. Louis fur prices jumped immediately.

At this same time, Wilson Price Hunt approached both Crooks and McClellen about a possible venture funded by John Jacob Astor to exploit the fur resources of the Columbia River Basin. Astor was proposing that one group would travel by ship around the Horn to establish the principal trading post near the mouth of the Columbia River. The other party was to travel overland up the Missouri River and then down the Columbia River. Astor was looking for dependable Americans to serve as leaders to the large number of French and Scottish Canadians, these being hired away from the North West Company for their experience.

April, however, was too late in the year to be organizing an expedition of this magnitude. It would have to wait until the spring of 1810. In order to secure the services of both Crooks and McClellen until the expedition was ready to depart, Hunt sent them upriver as agents for Astor to establish a post and relations with distant Indians and to start collecting furs.

Getting a license for the Upper Missouri River was no problem for Crooks and McClellen this year. Astor's venture was recommended to the attention of Governor Merriwether Lewis in a letter from President Thomas Jefferson. Obtaining trade goods was another problem. St. Louis' stocks of trade goods had been nearly depleted by the embargo. In order to obtain needed supplies, Crooks rushed back to Michilimackinac. After purchasing the goods, he again hurried back to St. Louis and then up the Missouri River to meet McClellen near the mouth of the Platte River. The goods were following, being brought up by Joseph Miller. Miller, with a keelboat load of goods, and about 40 voyageurs and trappers arrived in late August or early September. The party advanced another 350 or so miles to the vicinity of the James River (in what is now southern South Dakota), where their progress was halted by hundreds of angry Sioux Indians. The Sioux were upset because traders would invariably by-pass them for destinations further upriver. The Sioux had had enough, and this practice was going to end with Crooks and Miller.

Through deception, Crooks and McClellen were able to slip a few trappers upriver past the Sioux while at the same time moving the keelboat full of trade goods back downriver beyond the reach of the Indians. They opened a post for trade in the vicinity of Council Bluffs, but returns were poor and by spring of 1810 they had little to show for their efforts. Their future would depend on what they heard from Hunt, who had gone back to New York for detailed discussions with Astor.

Because it was still not certain that Astor would back a venture to the Columbia Basin, Crooks and McClellen formulated a backup plan. McClellen would build a post as far up the Missouri River as circumstances and Sioux Indians would allow, bartering for summer hides; meanwhile Crooks would return to Michilimackinac with their paltry harvest of pelts and make arrangements for a fresh supply of trade goods. The two partners were counting on Crooks encountering Hunt at Michilimackinac. If the Columbia River Basin venture was on, plans for the independent venture would be dropped.

In the meantime, Astor had agreed to fund a new company to exploit the fur resources of the Columbia Basin. The Pacific Fur Company was formed, with one hundred shares. Astor, who would conduct all dealings from the business end, and assume all financial risks including losses for the first five years, would hold fifty shares. Fifteen shares would be held in reserve, and and the remaining thirty-five shares would be divvied amongst the other partners, including Duncan McDougall, Donald McKenzie, William McKay, David Stuart, William Hunt, Robert McClellen, Joseph Miller and Ramsey Crooks. At 5 shares, the very junior Crooks would hold an interest equal to that held by the senior traders.

A two pronged effort would be pursued: a principal post would be established near the mouth of the Columbia by a sailing ship, the Tonquin, captained by Jonathon Thorn, who would proceeded around the Horn and thence up to the Columbia, while a brigade would proceed overland along a route similar to that taken by Lewis and Clark. The seaborne Astorians would be led by the partners Duncan McDougall, Alexander McKay and David Stuart, whereas Hunt would lead the overland Astorians. Crooks would be in Hunt's brigade.

Crooks learned these details when he met up with Hunt and McKenzie in mid-July 1810 at Michilimackinac. The party left Michilimackinac August 12th and reached St. Louis by September 3. Here they ran into difficulties hiring the experienced hunters they needed. Manuel Lisa and the St Louis Missouri Fur Company were planning another trip up the Missouri River, and demand for experienced men was extreme. It wasn't until October 21st that all preparations were finalized and Hunt's Overlanders departed St. Louis with two barges and a keelboat. (This Map shows of the events and route taken by the Westbound Astorians) The brigade proceeded as far as the mouth of the Nodaway River (now in the northwestern corner of Missouri) before winter forced a halt. Desertions over the winter forced Hunt to return to St. Louis to hire additional men. While there he hired an interpreter, Pierre Dorian Jr., agreeing to take Dorian's Iowa Indian wife, Marie and two children.

On Hunt's return to the Nodaway River Camp, he encountered John Colter, who was returning from the mountains. Colter described the hostilities encountered by Andrew Henry's brigade with Blackfoot Indians (one of the partners in the St. Louis Missouri Fur Company) in the Three Forks area. Colter advised Hunt to find an alternate way to cross the Rockies.

Hunt was back at the Nodaway Camp on April 17th, 1811, and on April 21st the entire brigade resumed its upriver journey. The brigade now included 60 men, three barges and one keelboat. The keelboat was armed with two small cannon and a swivel gun.

On May 26th, three more hunters were hired, John Hoback, Jacob Reznor and Edward Robinson. These three had also been with Andrew Henry the previous year and confirmed everything that Colter had relayed regarding the Blackfoot Indians. Hunt decided to abandon the Missouri River when the brigade reached the Arikara villages. The Arikara were known to have horses and if Hunt could trade for enough pack animals, the brigade could avoid the river and pack across the mountains.

On June 10th the brigade reached the Arikara villages. Trading for horses went slowly and it appeared unlikely that Hunt would obtain a sufficient number of horses from the Arikara. Lisa, whose brigade had earlier caught up with Hunt, offered to trade Hunt horses that Lisa had at a post further up river in exchange for Hunt's boats and some merchandise. Lisa wasn't being altruistic, but instead was motivated to see that Hunt's brigade made a clean break beyond the area Lisa intended to work. Crooks was tasked with going to Lisa's post to take delivery of the horses.

After a month at the Arikara villages, Hunt was ready to proceed by pack train. On July 18th, 1811, the brigade headed west towards the Rocky Mountains. Although highly experienced on rivers, few in Hunt's group had extensive experience with horses or pack trains. At the beginning progress was painfully slow until the brigade gained experience with the horses and packing.

By September 27th the brigade had reached the Snake River. Although the voyageurs were anxious to hollow out cottonwood trees for dug-out canoes (and to be rid of what to them were unpredictable horses) scouts had reported that there were long stretches of un-navigable water ahead. On October 8th the pack train rode down into the broad, meadowed valley of Pierre's Hole (Map showing the location of Pierre's Hole). It was apparent to the brigade that they had left the Rocky Mountains behind. The voyageurs prevailed and fifteen dug-out pirogues were constructed. The horses would be left in the custody of a couple of Snake Indians who promised to keep the horses until the Astorians returned.

Before the pirogues were finished, four hunters, Hoback, Reznor, Robinson and a Martin Cass, were sent out from the group. These men were to trap and assess the fur resources of the area on an extended hunting/exploration trip expected to last till the following spring.

Within the group, personal conflicts were beginning to take a toll: Joseph Miller decided he couldn't tolerate the company of the other partners. He gave up his shares in the company and joined with the party of hunters as a common trapper.

On October 19th, 1811, the brigade took to the river. Travel progressed rapidly for two days. The river was broad and swift, often more than a quarter of a mile wide. The few rapids were easily managed by the experienced voyageurs. On the third day (near present day Idaho Falls), basaltic cliffs compressed the river into a plunging cataract only sixty feet wide. The brigade portaged a mile and a half around the cataract and returned to the river. Progressively, the river plunged through ever deeper and more treacherous chasms. Finally a pirogue was lost and one man drowned. Down river, it was apparent that there were even more chasms. The next chasm they named Caldron Linn, Scottish for whirlpool. The river compressed from 800 yards wide, slammed over a narrow cascade into a monstrous whirlpool and then shot out through a narrow slot in the basalt cliffs not more than 40 feet wide. According to Robert Stuart "...at the Caldron Linn the whole body of the River is confined between 2 ledges of Rock somewhat less than 40 feet apart, and here indeed is terrific appearance beggars all description... ." No dug-out canoe would ever survive this.

Hunt sent out small groups to scout the north and south banks and assess the character of the river which they had committed themselves to. The scouts followed the river as far as thirty-five miles in the downstream direction. The reports were entirely gloomy. Hunt decided to quit the river entirely, but to do so he would need to once again obtain horses. Four men, under Reed were sent down river to see if they could find Indians who would trade horses. In the meantime, Hunt decided to have 16 of the best voyageurs test the water below Cauldron Linn. The results were abysmal: one dug-out was lost, the other three were hopelessly pinned by the current against rocks.

The weather turned foul, torrential icy rains poured down, food was running low, morale deteriorated and the group took to arguing. Reeds group had not returned, but this now seemed like too slim a hope to risk the future of the entire brigade. It was decided to send out additional parties: McClellen on the south side of the canyon, McKenzie to the north and Crooks to the east, to retrieve the horses left in the custody of the Snake Indians. The remainder of the brigade would stay beside the river and await developments. Crooks turned back after two days of painstaking toil through an unforgivingly rough country composed of deep ravines cut through a jagged basaltic lava flows. On November 6, 1811, two members of Reed's party returned with word that there was no sign of Indians in the country to the west.

Another desperation decision was made. It would be better to starve going forward as opposed to starving in camp. Two small groups might be easier to feed than a single large group. The bulk of the goods were cached, and the food and brigade divided. Hunt took 19 including Marie Dorian and the children on the north bank, and Crooks with 19 took the south bank. On November 9th in a freezing rain, the parties separated.

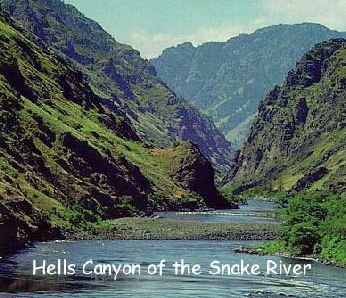

For 28 days Crook's party walked an average of 11-12 miles a day. Food was desperately

short, and for a ten day period the 20 men subsisted on one beaver, one  dog, some

chokecherries and boiled moccasin soles. By this time they were in what would come

to be known as Hell's Canyon. Unable to even attempt the snow choked Wallowa Mountains,

the weakened men descended to the river, determined to build rafts and float down

the river. On reaching the river, the boiling rapids made plain that this would

be impossible. While at the river edge, amazingly, white men appeared on the opposite

bank. It was Reed's and McKenzie's parties! Information could be shouted across

the river, but there was no way to cross the turbulent waters and the two groups

finally separated. Crook's party struggled for three days in waist deep snow. Finally

they decided that their only hope for survival was to return to an impoverished Indian

camp they had passed several days earlier.

dog, some

chokecherries and boiled moccasin soles. By this time they were in what would come

to be known as Hell's Canyon. Unable to even attempt the snow choked Wallowa Mountains,

the weakened men descended to the river, determined to build rafts and float down

the river. On reaching the river, the boiling rapids made plain that this would

be impossible. While at the river edge, amazingly, white men appeared on the opposite

bank. It was Reed's and McKenzie's parties! Information could be shouted across

the river, but there was no way to cross the turbulent waters and the two groups

finally separated. Crook's party struggled for three days in waist deep snow. Finally

they decided that their only hope for survival was to return to an impoverished Indian

camp they had passed several days earlier.

On December 6th, 1811 they saw Hunt's party on the opposite bank of the Snake River. Hunt's party had been managing somewhat better, having managed to trade for several horses from Indians. One of these had been butchered the previous evening, and there was some meat remaining. Hunt's men constructed a small, crude canoe using horsehide stretched over a frame of willow branches. One voyageur took the canoe across the river with a load of horsemeat, and returned with Crooks and a another man named LeClairc.. After consulting with Crooks, Hunt decided that both parties should return to the Indian village located in the vicinity of present day Wieser, Idaho. As soon as the decision was made, men in Hunt's party began to straggle off, singly and in small groups. Unable to keep up, Crooks attempted to return to his own party on the opposite side of the river, but the canoe had floated off. Two attempts were made to cross with a raft ended in failure, probably with Crooks being dumped in the freezing river.

Crooks became violently ill, and Hunt thought he would die. Overnight Crooks recovered somewhat, but was in no condition to travel. By this time there were only five men left with Hunt and Crooks, the remainder having wandered upriver in search of the Indian village. Hunt convinced two of his men to remain with Crooks and LeClairc, who was also ill, promising he would send help as soon as possible. On the December 10th, 1811 Hunt found Indians from whom he was able to purchase five horses and he promptly sent back horses and meat to the ill men. Somewhat recovered, Crooks, LeClairc and the others rejoined Hunt's party. Crooks party, who had still not been able to cross the river, had seen the purchase and butchering of some of the horses. Although they were crying out for food, none of Hunt's men were willing to risk the river. In outrage, Crooks ordered a canoe constructed, but in his weakened state, he collapsed while trying to launch it. His efforts though shamed the men, and Benjamin Jones, a hunter, and Joseph Delaunay each transported a load of meat across the river. As Delaunay was about to re-cross the river, one of Crooks voyageurs, demented by his sufferings, leaped into the canoe, tipped the craft, and drowned. Delaunay narrowly escaped the same fate.

John Day, one of Crooks party became convinced he was dying, and requested that he be allowed to spend his last hours with his bourgeois, Ramsay Crooks. Somehow Day was transported across the river. The scanty resources on both sides of the river had been exhausted, and Hunt was determined to move the men up to the Indian village on the Wieser River. Day would never be able to keep up. Unwilling to abandon the man, Crooks urged Hunt to keep the men together, that he would wait with Day until he either recovered or died and would then rejoin Hunt. Another ailing voyageur, Dubreuil requested that he be allowed to remain behind also. Some Shoshoni Indians promised to stay with the trio to help as they could, but eventually the Indians ran out of food and they drifted away.

Over the days, the condition of the ailing men worsened and death seemed certain for all. A couple of Indians wandered by, started a fire and then fed them a meal, before wandering on. Somewhat revived, Day managed to kill a wolf that had been prowling around the camp, which further improved the condition of the men. At this point three voyageurs appeared in camp. They informed Crooks that Hunt had found a guide to lead the brigade over the Blue Mountains and down to the Columbia River.

These three men had chosen to remain behind preferring the known miseries to fresh miseries. The voyageurs remained behind when Crooks, Day and Dubreuil finally felt able to follow Hunt's trail. Crooks and his party got lost in the Blue Mountains and wandered for weeks, being rescued and sustained from time to time by small bands of Indians, often not much better off then were Crooks and his men. One band agreed to care for Dubreuil when he collapsed completely. (Dubreuil would recover, returning to the Snake River where he lived with the Shoshone Indians, finally reuniting with a party of trappers detached from the brigade nearly a year earlier).

Crooks and Day staggered onward, finally reaching the Columbia River in mid-April. There an old Indian named Yeckatapam fed and sheltered them until they recovered their strength.

Crooks and Day traveled about 70 miles down the Columbia River, and had just passed the mouth of what is now known as the John Day River when they encountered a band of unfriendly Indians who robbed them of everything, guns, knives, fire steels, food and clothing. Naked and subsisting on rotting fish they found along the bank, Crooks and Day hobbled back upriver to Yeckatapam who clothed them and provided dried meat. Fearing the Indians downriver, and in a desperate mood, Crooks and Day decided to walk back to St. Louis. They were preparing packs of food, when four canoes, paddled by whites came by on the river. To the amazement of Crooks and Day, the canoes were paddled by men from John Reed and Robert McClellen's parties.

From these men Crooks learned of the disasters which had befallen Reed, McClellen and McKenzie who were the first of the Overlanders to reach Astoria in mid-January of 1812. McClellen had decided that the hardships and dangers were not worth the company shares which he had been alotted and he had given up his partnership in the venture, vowing to return home at the first opportunity. On March 22, 1812 three groups of men had set off from Astoria, to relieve and resupply a post on the Okanogen River, retrieve goods cached at the Caldron Linn, and to find Crooks, Day and Dubreuil. They were unsuccessful in recovering the cached goods or finding Crooks and his men, but they had met up with a party of trappers sent upriver the previous fall from Astoria. These men had had a successful harvest of 2,500 beaver pelts. The pelts were loaded and the group started back to Astoria when they had been hailed by Crooks and Day.

The men returned to Astoria by May 11 or 12, 1812. John Jacob Astor's supply ship "Beaver" was in and goods and fresh men were being disembarked. With the appearance of 2,500 beaver pelts, and favorable reports of the fur resources of the Columbia River Basin, enthusiasm for the venture returned. However, after a meeting of the remaining field partners on May 14, Crooks too decided to give up his shares in the company. It is not known why Crooks was willing to relinquish his stake in the company. In spite of the almost euphoric mood at Astoria, there were still major obstacles to success: unfriendly Indians, commercial pressure from the North West Company, the Non-Intercourse Act with Britain and France; and looming war with Britain may all have been part of his considerations. Perhaps the hardships he had endured along the Snake River that winter had also taken a toll on his spirit.

Both Crooks and McClellen now awaited an opportunity to return home. Hunt had assumed command of the entire operation. Four new posts were planned up the Columbia River and the post on the Okanogen was to be reinforced. Another attempt was to be made to recover the cached goods near Caldron Linn and finally, Robert Stuart was to deliver dispatches back to Astor in New York. Crooks and McClellen would accompany Robert Stuart and his party.

The different expeditions set off together on June 29, 1812. (Map showing Stuart's eastbound route) Shortly after leaving Astoria, John Day went mad. According to Stuart's journal, Day began muttering "the most absurd and unconnected sentences" and Day reviled every Indian he saw "by the appellations of Rascal, Robber & C & C & C." After Day had put two pistols to his own head and pulled the triggers, amazingly missing both times, his companions bound him and kept him under constant guard until some Indians were found near the mouth of the Williamette River to return him to Astoria. Day eventually recovered and until his death in 1820 he was a productive trapper in the employ of the North West Company.

At the mouth of the Walla Walla River, Stuart's small party traded for horses and on July 28th struck off overland in a southeasterly direction for the Snake River. Enroute they suffered greatly from heat and thirst until arriving at the Blue Mountains. They proceeded through the Blue Mountains along a route similar to that taken by Crooks and Day the preceding winter. While traveling along the Snake River Plain, the party stumbled across Hoback, Reznor, Robinson and Miller, hunters who had been dispatched to trap the previous year. Martin Cass, who had been with the hunters had disappeared during their wanderings. The hunters had experienced fair success trapping but had been robbed of everything by Arapahoe Indians, and for weeks had barely managed to survive. When the combined party reached the supply caches at Caldron Linn, they found that six of the nine caches had been opened and plundered. Hoback, Reznor and Robinson were happily re-equipped from the stores and returned to trapping. Miller, however, had had enough of hardships in the wilderness and desired to return to civilization.

Crow Indians stole every horse the party had somewhere near the present day Idaho-Wyoming border, leaving the party afoot. At one point in their trek the men had gone so long without food that one of the voyageurs suggested cannibalism by lot. Before the merits of the proposal could be debated, Robert Stuart ended the discussion by cocking his rifle and threatening to put a ball through the skull of the next man to broach the subject. The following day an old bull buffalo was killed: the men were so ravenous that they ate the animal raw.

By early November 1812, the party had reached the vicinity of present day Casper, Wyoming where they decided to halt for the winter. Buffalo were plentiful, and the men built a hide covered hut. In mid-December the party moved about 150 miles down to the North Platte River after taking a scare from Arapaho Indians. There they constructed another hut. New Years Day was celebrated feasting on buffalo tongue and smoking Joseph Millers tobacco pouch.

In early March, 1813 the men attempted to float down the shallow Platte River, but after much struggling with little progress, they resumed trekking across the plains on March 20. When they reached present day eastern Nebraska, they learned that war had broken out between the United States and Britain, but the available details were confusing and contradictory. When they reached the Missouri River they found a dugout canoe, and constructed a hide canoe. With these craft they were able to commence floating down the river. At Fort Osage they learned that war had been declared in June of 1812, before they had even departed Astoria.

They arrived in St. Louis at sunset on April 30th, 1813. To these men it must have seemed as if the world had been turned upside down in the three years that they had been gone. The entire Great Lakes region was under British military control. Michilimackinac was in enemy hands. The Indians were up in arms, flocking to join the British in the war against the Americans. Fur prices had plummeted and the very future of the fur trade must have seemed in doubt. Crooks, now 26 years old, had spent the last eight years in the wilderness, with little to show for his efforts except experience.

During the early part of July, 1813, Crooks set off for New York City to meet with John Jacob Astor. Crooks still had great enthusiasm for the fur potential of the Upper Missouri Country and Northern Rocky Mountain Region but Astor would have none of it. Astor imagined that immense quantities of furs were piling up in warehouses and storage depots all over the Great Lakes Region, unable to move because of the War. Astor wanted someone to go into the region to plot a course between commercial rivalries, military hostilities, and warring Indians and liberate these furs for Astor. Astor felt that Crooks was the perfect person: Crooks was born a Scotsman, but was also a naturalized American citizen, Crooks had traveled extensively through the region and had an immense knowledge of the geography, and he had personal and business relationships with many of the personalities of the region. In spite of his personal qualifications, by the end of the war, Crooks had not had any notable success in obtaining furs in the Great Lakes Region.

After the war, Crooks continued to work for Astor, primarily in the Great Lakes Region, eventually rising to the number two position, after Astor, in the American Fur Company. Astor sought to dominate the fur trade in the region, but competition remained fierce. When competition was too strong to be crushed outright, The American Fur Company would co-opt them in a partnership relationship within the company. By 1823, the American Fur Company had consolidated its hold on the region, including the Great Lakes Region, the Upper Mississippi Region, and the Mississippi River down to St. Louis. Crooks still wanted to expand into the Upper Missouri River Region, but the now risk averse Astor continued to hold him back. Dominance of the American Fur Company in its trading regions did not end its conflicts: external commercial competition often became internalized between the junior partners in the company. Crooks responsibilities more often came to include the role of peacemaker and mediator between the different partners.

Ramsay Crooks, at a time when he was 38 years old, would marry Emilie Pratte, daughter of Bernard Pratte, a powerful and well connected fur trader in St. Louis. Although Emilie had been born and raised in St. Louis, the new couple would set up housekeeping in New York City.

In December of 1826 Crooks would accomplish his goal of extending the company's reach into the Upper Missouri River Region. A partnership with the Bernard Pratte & Company (Pratte was now his father-in-law) was to start effective July 1, 1827 for operations up the Missouri River. Crooks was to be General Superintendent of Affairs, but the Western Department (as the new unit was to be known) was not to be bound by Crooks decisions if their experience indicated otherwise. Pierre Choteau would actually run operations for the Western Department. Also, the Columbia Fur Company under Kenneth Mackenzie, was to be brought into the American Fur Company at this time. The Columbia Fur Company had proven to be a tenacious competitor with both the American Fur Company and with Bernard Pratte & Company by operating outfits in both the Upper Mississippi River and Missouri River Regions. After the merger, the Mississippi River outfits would be joined with Astor's outfits to form the Northern Department. Mackenzie and other excess employees would be sent to the Upper Missouri River to establish new posts high up the river and would operate as the Upper Missouri Outfit (the UMO) under the Western Department.

Although Mackenzie brought much energy and experience to the operation, and was a highly successful trader, his extremely aggressive tactics, including skirting or even outright breaking laws, especially with regards to alcohol proved to be a source of nearly constant embarrassment to the Western Department. Crooks often found himself in Washington explaining, denying or attempting to minimize damages resulting from the excesses of Mackenzie and other over-zealous traders.

In the years leading up to 1834, John Jacob Astor had been giving indications that he wanted to sell his interest in the American Fur Company and get out of the fur business. In April of 1834 final papers were signed. The Western Department would revert to Pratte, Choteau & Company (in the West, it would still be generally known as the American Fur Company). Crooks became president of the American Fur Company, which at that point consisted mostly of the Northern Department.

As president of the American Fur Company, Crooks was ruthlessly competitive. There would be no more coming to terms with rival outfits, and no more buyouts. The company's most serious opposition came from the Ewing brothers of the Wabash County area. For a time, both firms practiced a type of mutual self-annihilation in a profitless fight to control the trade. When the European fur market broke in 1842 Crooks sold off the Mississippi outfit to Pierre Choteau. It wasn't enough, and when a treaty, which might have allowed the company to collect from the government for bad credits advanced to Sioux Indians failed to be approved, the company suspended payments on its debts of some $300,000. However, by judicious maneuvering and deal-making, Crooks was eventually able to satisfy all of the companies creditors.

In 1845 Crooks opened a small commission house in New York, dealing in all kinds of furs. He lived quietly and his principal pleasures were in meeting old friends from the wilderness years.

Crooks apparently never attempted to record the story of his years in the fur trade. The only time he published even a fragment of his experience was during the 1856 presidential campaign, when a publicist for John C Fremont was claiming that Fremont had discovered the South Pass. Crooks wrote to set the record straight, stating that a party of Hunt's Overland Astorians had traversed the pass in 1812, thirty years before Fremont set foot on the pass.

Ramsay Crooks died on June 6, 1859. According to the New York Herald, "He seemed to die of no particular disease. He quietly passed from the world as one retired to sleep." Ramsay Crooks was seventy-two years old.

To learn more about Ramsay Crooks see the following references:

The Fist in the Wilderness, by David Lavender, 1964, published by the University of Nebraska Press.

The Fur Trade, by Paul Chrisler Phillips, published 1961, University of Oklahoma Press, two volumes, approximately 1400 pages.

The Mountain Men and the Fur Trade of the Far West, Volume IX; edited by LeRoy R Hafen, published by The Arthur H Clark Company, Glendale, California, 1966.

Back to the Top

Back to the Men