Subject Guide

Mountain West

Malachite’s Big Hole

Beaver, Furs, Skins and Robes

The fur trade in North America was driven by European demand for skins and furs of

all types. Increasing wealth and higher living standards in Europe starting in the

14th and 15th centuries brought a desire for clothing which was both comfortable

and fashionable. Textiles at the time were both coarse and rough, and colors were

few. Furs, by comparison, were soft and warm, and leather clothing was comfortable,

sturdy and durable. So great  was the demand in Europe, that by the fifteenth century,

the harvest of wild, native fur-bearing animals was no longer sufficient to meet

demand for leather and furs. At this time, exploration and colonization of North

America opened up the vast fur and skin resources of that continent. For two hundred

years, Indians provided the labor to harvest the furs and skins, in trade for iron

and steel weapons and tools, brass, silver and glass ornaments and textiles.

was the demand in Europe, that by the fifteenth century,

the harvest of wild, native fur-bearing animals was no longer sufficient to meet

demand for leather and furs. At this time, exploration and colonization of North

America opened up the vast fur and skin resources of that continent. For two hundred

years, Indians provided the labor to harvest the furs and skins, in trade for iron

and steel weapons and tools, brass, silver and glass ornaments and textiles.

Beaver: All types of skins and furs were in demand but the most sought after included deer, muskrat, buffalo, raccoon, otter and bear. Interestingly, one year it is recorded that the American Fur Company made a shipment of furs to St. Louis which included 1,500 prairie dog skins. (This shipment of prairie dog skins was apparently a market test for gloves, cuffs, etc. The fact that there were no further shipments of prairie dog skins suggests that there was little demand for the diminutive skins.) However, the fur of the beaver was especially desired and premium prices were paid for its skin. Beaver fur has long been known for its superior felting qualities. Pressed together with steam or hot water the fine fur (wool) became felted cloth, valued especially for fashionable hats. Beaver headpieces become so valuable that they were willed by fathers to eldest sons. In France, beaver hats gained such status that generous trade-ins were allowed for worn models on new purchases. The used hats were sold in Spain, then trimmed of the most worn parts for resale in Portugal, and finally they were traded for ivory in Africa. The fur of the beaver was so precious for hat making that the sand from the floor in the warehouses where the pelts were stored was sifted to salvage every last hair. By the 1500's the beaver was essentially extinct throughout Europe. Only small populations remained in northernmost Siberia and remote parts of Scandinavia. On the arrival of European explorers to the new world, the American beaver became the soft gold of the French, English, Dutch and later the Americans.

Beaver live in and near streams, rivers and ponds. They are excellent swimmers and

can swim underwater for one-half mile and go without breathing for up to fifteen

minutes. Adult beaver range in size from three to four feet, including the tail.

On average beaver weigh 50 to 60 pounds, but may be as large as 110 pounds Unlike

most other kinds of mammals, beavers continue to grow throughout their lives. Beaver

live in family groups, generally consisting of six individuals, but may number as

many as twelve.

but may be as large as 110 pounds Unlike

most other kinds of mammals, beavers continue to grow throughout their lives. Beaver

live in family groups, generally consisting of six individuals, but may number as

many as twelve.

Beavers are relatively slow and awkward on land, but can easily evade predators in

the water. They build dams and canals so that additional areas are accessible to

them within easy reach of water. Dams may be up to 8 feet high and dams of more

than 1,000 feet in length are not uncommon. Canals are dug to move logs to dams

or lodges easily and quickly. Canals are 12 to 18 inches deep and 18 to 24 inches

wide, and may run for 700 feet.

Beavers live in dome shaped lodges constructed of mud and branches. The lodges generally are constructed in the middle of the beaver pond behind the dam, although some may be constructed on the bank. The lodge generally has multiple underwater entrances, leading into an inner living chamber four to six inches above the water.

Trapping Beaver: The presence of beaver could always be determined from well maintained dams and lodges along a stream or river. The trapper, having found fresh beaver sign, would concentrate his trap-setting along waters that the animals frequented. When a likely spot was found for a “set”, a bed for the trap was prepared underwater in such a manner as to assure that the pan and spread of jaws of the trap would be about four inches below the surface of the water. After the trap had been adjusted on the underwater bed, the trap chain was extended its full length outward to deeper water, and a trap stake was driven deep into the bottom sediments and a “float stick” was passed through the ring at the end of the chain. Usually the chain ring was tied to the stake with a strong cord to ensure that should the stake be pulled loose by the captured beaver, the stake would remain tied to the trap. The final step was the placement of the “bait”. A pliable stick was cut to a length that would permit the stick to extend from the stream bank to directly over the pan of the trap. Castoreum was smeared on the end of the stick by the trapper from a bait bottle which he carried. Then the other end of the bait stick was jammed into the soil of the stream bank, and adjusted so its end was suspended six inches above the water at the set. The trapper then waded from the water some distance from where the set was made.

Beaver are very territorial animals, and each has a uniquely scented castoreum. The scent of an intruder's castoreum is irresistible to the beaver, and it would attract beaver in the area to investigate the baited stick. The cautious beaver would approach from deep water, and getting close would lift it’s nose to investigate the bait, setting one or both front feet on the pan of the trap, triggering it. The frightened animal would then dive to deep water for safety, taking along the heavy trap with it. Eventually the weight of the trap drowned the beaver at the bottom of the pond where it's carcass would await the trapper when he made the next round of his sets.

Skinning the Beaver: Skinning was always done in the vicinity where the animal was

trapped, and generally only the pelt, and perhaps the castoreum glands were carried

back to camp. If the trapper was working out of a large camp, he might be able to

turn over his freshly skinned pelts to a camp keeper for stretching and drying. If

the party was small, the task  of fleshing and stretching the pelt would be done by

the trapper himself. After the pelt had been removed from the carcass, it was scraped

with a sharp knife or ax blade to free it from fat and shreds of flesh. In order

to dry it quickly and uniformly, it was stretched in a hoop made by bending a supple

willow branch of the appropriate size into a circular form and then tying the ends

together. The skin was then sewed with sinew around the edges and attached to the

hoop. When dry the pelt resisted attacks by insects and spoilage. Beaver skins

were not dressed or tanned Rufus Sage (Reference) writes in the 1840's "The usual

mode of dressing skins, prevalent in this country among both Indians and whites,

is very simple in its details and is easily practised. It consists in removing all

the fleshy particles from the pelt, and divesting it of a thin viscid substance upon

the exterior, known as the "grain;" then, after permitting it to dry, it is thoroughly

soaked in a liquid decoction formed from the brains of the animal

of fleshing and stretching the pelt would be done by

the trapper himself. After the pelt had been removed from the carcass, it was scraped

with a sharp knife or ax blade to free it from fat and shreds of flesh. In order

to dry it quickly and uniformly, it was stretched in a hoop made by bending a supple

willow branch of the appropriate size into a circular form and then tying the ends

together. The skin was then sewed with sinew around the edges and attached to the

hoop. When dry the pelt resisted attacks by insects and spoilage. Beaver skins

were not dressed or tanned Rufus Sage (Reference) writes in the 1840's "The usual

mode of dressing skins, prevalent in this country among both Indians and whites,

is very simple in its details and is easily practised. It consists in removing all

the fleshy particles from the pelt, and divesting it of a thin viscid substance upon

the exterior, known as the "grain;" then, after permitting it to dry, it is thoroughly

soaked in a liquid decoction formed from the brains of the animal  and water, when

it is stoutly rubbed with the hands in order to open its pores and admit the mollient

properties of the fluid, - this done, the task, is completed by alternate rubbings

and distensions until it is completely dry and soft." The photo at right is a fleshing

tool that might have been used by either a trapper or an Indian.

and water, when

it is stoutly rubbed with the hands in order to open its pores and admit the mollient

properties of the fluid, - this done, the task, is completed by alternate rubbings

and distensions until it is completely dry and soft." The photo at right is a fleshing

tool that might have been used by either a trapper or an Indian.

Making a Pack: As the dried beaver pelts accumulated in camp, they were pressed

in to compact bundles, called a pack, to ease handling. Dried pelts generally weighed

about 1 and ½ pounds each. The pelts were  folded in the center, fur side in, and

pressed into a pack encased in a wrapper of deer skin or other less valuable material.

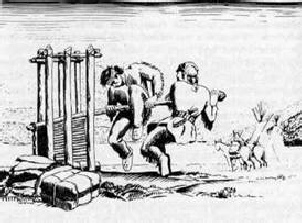

The drawing at left (by Mulcahy, Jefferson National Expansion Memorial, St. Louis)

shows how trappers in the field would have compressed pelts into a pack. About 60

pelts went into each pack, with a total weight of about 100 pounds. Each pack was

valued at $300 to $600 dollars, depending on the market conditions. A pack animal

could carry two packs. (Consider that gold was worth $20 an ounce, and a

folded in the center, fur side in, and

pressed into a pack encased in a wrapper of deer skin or other less valuable material.

The drawing at left (by Mulcahy, Jefferson National Expansion Memorial, St. Louis)

shows how trappers in the field would have compressed pelts into a pack. About 60

pelts went into each pack, with a total weight of about 100 pounds. Each pack was

valued at $300 to $600 dollars, depending on the market conditions. A pack animal

could carry two packs. (Consider that gold was worth $20 an ounce, and a working

farm could be purchased for around $1,500 at this time). At the end of the spring

hunt, the fur packs would be sent back to St. Louis by pack train, or by boat. If

the furs were sold to a large company that maintained a trading post in the area,

the packs might be opened, the pelts reconditioned and thoroughly dried, and then

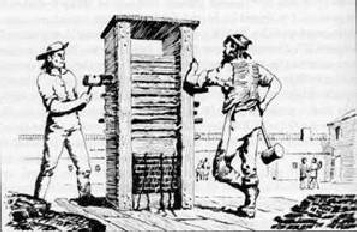

repacked using more powerful presses. A wedge press is shown to the upper right

(by Mulcahy).

working

farm could be purchased for around $1,500 at this time). At the end of the spring

hunt, the fur packs would be sent back to St. Louis by pack train, or by boat. If

the furs were sold to a large company that maintained a trading post in the area,

the packs might be opened, the pelts reconditioned and thoroughly dried, and then

repacked using more powerful presses. A wedge press is shown to the upper right

(by Mulcahy).