Subject Guide

Mountain West

Malachite’s Big Hole

Fort Hall:

Nathaniel Wyeth was a New England ice merchant who had come west in 1832 to establish a commercial empire based on Rocky Mountain furs, and Columbia River salmon. Wyeth first went to the mountains in 1832-33 on what was essentially a fact finding expedition, to gain first hand knowledge of the opportunities. After the rendezvous of 1833 Wyeth entered into a secret contract with the Rocky Mountain Fur Company and Christy to provide supplies and equipment to the company at the 1834 Rendezvous. The Rocky Mountain Fur Company and Christy at that time was deeply in debt to William Sublette and Robert Campbell, who had previously supplied them, and the company was now seeking a means of breaking the financial strangle-hold that Sublette and Campbell had established.

William Sublette became aware of the secret deal when a letter addressed to Milton Sublette, one of the partners of the Rocky Mountain Fur Company and Christy was delivered erroneously to William, his brother.

In another deal between the St. Louis Fur Company belonging to William Sublette and Campbell and the American Fur Company, Sublette had assured the American Fur Company that the Rocky Mountain Fur Company and Christy was on the brink of insolvency, and would soon go under. If the Rocky Mountain Fur Company were to obtain cheaper supplies, this condition of the deal between the St. Louis Fur Company and the American Fur Company would be endangered. Sublette and Campbell would have to go to the mountains to call in their debts from the Rocky Mountain Fur Company and Christy.

In the spring of 1834 there ensued a race to the mountains between competing supply trains. Nathaniel Wyeth would leave Independence on April 28, 1834, with a pack train of 75 men and about 250 horses. This number would include Milton Sublette, Osborne Russell, Jason Lee, a Methodist missionary and his four companions, and two naturalists, Thomas Nutall and Kirk Townsend. Milton Sublette would return to Independence on May 8th because of a diseased leg which would later be amputated.

William Sublette would not leave Independence until May 5th, seven days after Nathaniel Wyeth. William Sublette’s party consisted of 37 men and 95 horses. The supply trains would take the familiar route up the North Platte, then up the Sweetwater and over South Pass. William Sublette with his long experience in packing supplies to the mountains would easily overtake and pass Nathaniel Wyeth, who was also burdened with the missionaries and naturalists, on May 12, just seven days after leaving St. Louis. Wyeth, though was a quick learner, and Sublette arrived at rendezvous only a few days ahead of Wyeth.

At the time that Sublette passed him, Wyeth forwarded a letter ahead to Thomas Fitzpatrick imploring him not to trade with William Sublette, and telling Fitzpatrick that Wyeth’s train would be at rendezvous no later than July 1st. William Sublette made contact with Thomas Fitzpatrick on June 15th. On June 19th, the combined parties would move up to Ham’s Fork, a tributary to Black’s Fork of the Green River.

Wyeth would arrive on June 18th at the confluence of the Sandy and Green River’s, the agreed location of the rendezvous, to find no one present. Traveling upstream, he found the encampment of Fitzpatrick and William Sublette. To his disappointment, the Rocky Mountain Fur Company broke its contract with him, and refused his goods. William Sublette had called in the debts owed by the partners of the Rocky Mountain Fur Company, thus forcing it into insolvency. Wyeth expresses his feelings in a letter dated July 1st to Milton Sublette back in St. Louis, “…Now Milton, business is closed between us, but you will find that you have only bound yourself over to receive your supplies at such price as may be inflicted and that all you will ever make in the country will go to pay for your goods, you will be kept as you have been a mere slave to catch Beaver for others.”

Although he was able to trade some of his goods to Indians and free trappers, Wyeth was left with a large quantity of trade goods and supplies. Wyeth is reported to have said to the partners of the Rocky Mountain Fur Company “I will roll a stone into your garden which you will not be able to get out.” With his surplus goods, Wyeth intended to move west across the mountains and set up a trading post in the valley of the Snake River to trade with Indians for furs and skins.

Wyeth reached the Snake on July 14, 1834 and chose a site for his fort about a hundred and fifty yards from the river, at a point several miles north of the Portneuf River. (see the location of Fort Hall on the Fur Trade Rendezvous Map) His men went to work right away, erecting two houses and some horse corrals enclosed in a stockade 15 feet high and 80 feet square. Complete with bastions for defense, his fort was well located in the center of both Shoshoni and Bannock Indian wintering grounds of the upper Snake valley.

Upon completion of the fort, Wyeth's men were allowed to celebrate. John Kirk Townsend recorded the following description: "August 5th. At sunrise this morning, the "star-spangled banner" was raised on the flag-staff at the fort, and a salute fired by the men, who, according to orders, assembled around it. All in camp were then allowed the free and uncontrolled use of liquor, and, as usual, the consequence was a scene of rioting, noise, and fighting, during the whole day; some became so drunk that their senses fled them entirely, and they were therefore harmless; but by far the greater number were just sufficiently under the influence of the vile trash, to render them in their conduct disgusting and tiger-like. We had "gouging," biting, fisticuffing, and "stamping" in the most "scientific" perfection; some even fired guns and pistols at each other, but these weapons were mostly harmless in the unsteady hands which employed them."

After the fort was established, Wyeth left behind a dozen men, fourteen horses and mules, and three cows to continue trade with the Indians and to trap the surrounding country. Wyeth and the remainder of his men proceeded on to the lower Columbia to develop his projected fisheries and to pursue other business opportunities with the Hudson’s Bay Company.

Wyeth was aware that in order to succeed with Fort Hall he would need to procure supplies and goods brought up from the lower Columbia basin. However, he was unable to either independently develop such a supply system, or develop a cooperative arrangement with the Hudson's Bay Company, which already was operating from Fort Vancouver on the lower Columbia.

The Hudson’s Bay Company declined to cooperate with Wyeth, leaving Wyeth with few alternatives. In May 1836, he decided to sell Fort Hall to the Hudson's Bay Company. It would be a year before the deal was finalized. Wyeth's plan to obtain control of the Rocky Mountain fur trade by supplying Fort Hall from the lower Columbia River basin ultimately worked out just as he anticipated it would, but it would be the Hudson’s Bay Company which would make the plan succeed and reap the profit from it. The Hudson’s Bay Company assumed control of the post on June 16, 1838.

Rather than depend solely upon parties of mountain men for trade, they decided to employ the local Indians if they could persuade them to engage in fur hunting. The Hudson’s Bay Company relied on the Indian trade to a greater extent than did the previous American owners, but the company still sent out fur brigades of company employees and free trappers to work the surrounding country.

With the decline of the annual summer rendezvous, the mountain men who had previously been supplied out of St. Louis, would now be served by Fort Hall. American fur trappers continued to frequent the post after it had been sold to the Hudson’s Bay Company. They had always done business at this location while under Wyeth, and it was just too convenient to give up, even if it meant trading with a British Company. T. J. Farnham noted in 1839 as the fur trade was in decline that "the American trappers even are fast leaving the service of their countrymen, for the larger profits and better treatment of British employment." Goods could be now be purchased at Fort Hall for half the price charged at American posts supplied from St. Louis; furs could be sold there for more than they would bring elsewhere. The fort had a two-tier price system: white trappers, who had access to other markets, got more for their furs than the Indians received, and paid less for their supplies.

Attempts to make Fort Hall more self-sufficient--commenced in Wyeth's time with efforts at raising onions, peas, corn, and turnips--and continued under the Hudson’s Bay Company. Transportation costs for goods and supplies brought in were extremely high; and anything which could be locally grown, produced or manufactued would greatly increase the profitability of the post. A plow was brought in 1839, but dry weather ruined the wheat crop. Cattle, traded after 1842 from emigrants on the Oregon Trail, did thrive around Fort Hall.

Moreover, the fur trade itself prospered at Fort Hall after it had declined in the Rockies generally; during the winter of 1842-1843, Fort Hall and Fort Boise were responsible for 2,500 beaver, which helped that season "to make up for losses elsewhere." In 1845-1846, the Snake country fur trade (1,600 beaver) still was valued at $3,000.

By 1842 much of the Fort Hall trade depended upon supplying emigrant traffic to Oregon and California. Wagon trains could reach Fort Hall from the Missouri valley with no particular difficulty. Taking wagons farther west proved to be more of a problem. Henry Spalding and Marcus Whitman had brought a wagon past Fort Hall in 1836, but it had to be modified as a cart to get it as far as Fort Boise where it was abandoned altogether. Hudson's Bay traders had managed to haul Spalding's wagon over the Blue Mountains to Fort Walla Walla in 1840. But they had such a hard time that they concluded that the pack trail from Fort Hall to the Columbia River simply wasn't practical for wagons.

Small emigrant pack trains made their way from the Mississippi Valley via Fort Hall to the Columbia in 1839-1840 and in 1841. Then in 1842, a larger group of 137 emigrants showed up with wagons. On the suggestion of Richard Grant, Hudson's Bay Company chief trader in charge of Fort Hall, they left the wagons at his post, and packed the rest of the way. Grant was able to sell them flour for the rest of their journey at half the price they had to pay at Fort Laramie; he traded for the abandoned wagons as an accommodation to the travelers. The emigrant supply trade increased enormously the next year with close to a thousand people coming through. By that time, Grant's problem, in the face of desperate demand, was to keep back enough provisions to get Fort Hall through the winter.

Unable to continue westward from Fort Hall without wagons, the emigrants accepted Marcus Whitman's advice to force their way through. They succeeded in getting their wagons clear to the Columbia. Each year after that brought another wave of emigrants on their way to Willamette Valley. In 1846, partly in response to continued emigrant traffic, the Snake country became part of the United States. Pending a settlement of Hudson's Bay Company claims for posts in that part of Oregon assigned to the United States, though, Fort Hall continued to function as a British post.

Practically a complete shift from fur trade to emigrant trade followed not long after the boundary settlement. Extensive Mormon migration in 1847 to Salt Lake gave Fort Hall an unexpected new market for several years, until the Mormon settlements became self-sufficient. A dip in emigrant wagons from 901 in 1847 to only 318 in 1848 came just before the end of the fur trade. Then the California gold rush improved the situation abruptly. Even though much of the 1849 traffic was diverted southward over Hudspeth's Cutoff, Richard Grant estimated that 10,000 wagons rolled past Fort Hall that summer. At the same time, a force of mounted riflemen established a short-term United States military post--Cantonment Loring--only about six miles from Fort Hall in August.

Declining beaver prices, combined with a profitable emigrant trade on the Oregon and California trails, brought the fur trade at Fort Hall to a sudden halt in 1849. The beaver market in London had collapsed to the point that the Fort Hall rates (one Hudson's Bay Company blanket for four beaver) had become entirely too high, and the fur trade there turned out to be "more than unprofitable."

Both the Indians and mountain men based at Fort Hall could now earn a living through trade with passing emigrants. Richard Grant reported February 22, 1850, that "the Indians have become Careless, and still more indolent than they ever were in hunting furs--some of the Old Ones no doubt might be enticed to hunt Beaver but that once valuable Animal having now [become] valueless, they are not encouraged." The Indians, in fact, now had to hunt large animals for subsistence as well as for the emigrant trade. From 1849 on, Fort Hall had little function except as a supply post for wagon trains bound for Oregon. With Hudspeth's Cutoff (1849) diverting the California traffic, along with many of the Oregon wagons as well, to a route farther south, Fort Hall entered an abrupt decline.

Even though great Snake River floods damaged Fort Hall severely in 1853, and much of the emigrant traffic bypassed Fort Hall, the British company hoped to continue to supply travelers on the Oregon Trail. Wagons began to haul flour and trade goods from the Lower Columbia to Fort Hall in 1853, and pack trains were discontinued altogether on the supply route in 1854.

Indian trouble along the Oregon Trail broke out near Fort Boise in 1854, however, and by 1856 the situation deteriorated so terribly that all personnel at Fort Hall had to be withdrawn. A decade later, a general settlement of Hudson's Bay Company claims for the value of posts in the United States was arranged. British interests at Fort Hall thus came to an end just at the time that establishment of an Indian reservation led to the development of a new and different kind of Fort Hall. By that time, Fort Hall also had become a station for stage lines hauling passengers to the new gold fields. Travelers still came by, but they no longer had to find their way through the great uninhabited wilderness that had faced earlier emigrants on the Oregon and California trails.

The fort was finally abandoned in 1855, but emigrants continued to camp in the abandoned buildings and graze stock in the pastures until 1863. That year, extraordinary floods swept away the final remaining structures of the fort.

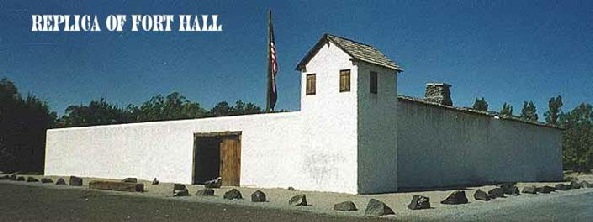

The original site of Fort Hall is on private property today, but a replica has been built in the city of Pocatello where visitors may see how one of the later versions of the fort looked.