Subject Guide

Mountain West

Malachite’s Big Hole

A Comparative Analysis of the 1837 Fort Jackson Trading Camp Inventory

©Michael Schaubs 2013

A version of this article appeared as a three part series in Journal of the Early Americas Vol III, Issues II, III and IV.

On December 2, 1837 a trading party under James C. Robertson left Fort Jackson to trade on the Arkansas River.1 It’s likely that the purpose of the party was to trade with the Cheyenne Indians in the vicinity of Big Timbers (located a few miles west of present day Lamar, Colorado), this being a favored wintering location for these Indians. A further purpose of the trading party may have been to tweak the Bent, St. Vrain & Co (BSVC), whose primary trading center, Bent’s Fort was located approximately 60 miles upriver. While many details of the trading party have been lost, the inventory of trade goods with wholesale prices has been preserved. The items listed on the Fort Jackson inventory (FJI) have been grouped into functional categories and compared to a statistically valid data set represented by French trade goods in the Western Great Lakes Region for years between 1715 and 1760.2

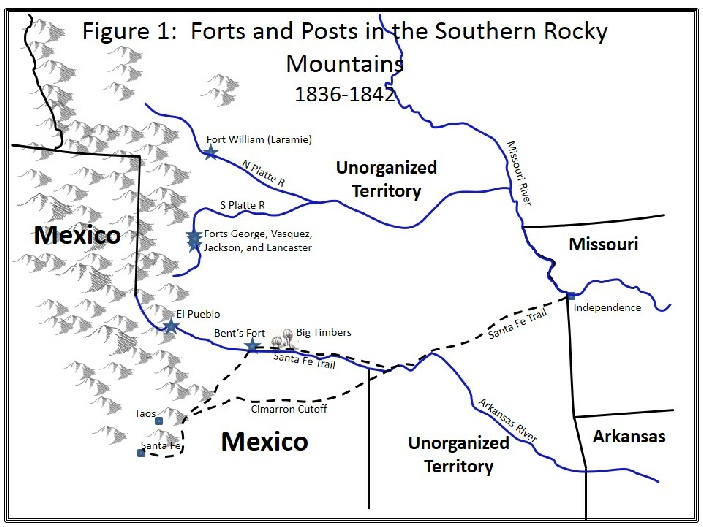

The location of Fort Jackson is uncertain, but is believed to have been several miles to the south of present day Platteville, Colorado, on the east bank of the South Platte River. The valley of the South Platte River running along the front range of the Rocky Mountains was in many ways an ideal location for a trading post. This area, located approximately midway between Fort William (starting to be known as Fort Laramie in 1838) on the north and Bent’s Fort on the south, had an abundance of food resources including buffalo and wild berries that drew large populations of Indians to the area. In their own tongue, the Cheyenne people referred to the South Platte as the “Tallow River.3” Shallow deposits of coal cropped out in the area, which could be mined from the surface providing fuel for blacksmithing and heating4. Low cost labor was available from Mexican Taos and Santa Fe5 and a generally mild climate were additional positive characteristics of the area. Figure 1 shows the locations of natural and cultural features as they existed in 1837.

The first trading post constructed in the area was Fort Vasquez in 1835. Operated by Louis Vasquez and Andrew Sublette, the partners received financial backing from longtime fur trade entrepreneurs William Sublette and Robert Campbell. William Sublette and Campbell may have provided financial backing because they believed that there were still openings for a small company to thrive in the fur trade. However, these two men had a long history of annoying the American Fur Company (AFC), and this may have been simply another opportunity to irritate their long standing rivals. Both the BSVC and the AFC swiftly responded to the commercial challenge offered by Fort Vasquez by constructing Fort George (aka Fort Lookout or Fort St. Vrain) and Fort Jackson respectively. Operations at Fort Jackson were managed by Peter Sarpy and Henry Fraeb, both highly capable men with long experience in the fur trade. At about this same time, Lancaster Lupton, a former Army Lieutenant who had traveled through region with Colonel Henry Dodge in 1835, also chose this area as a location for his Fort Lancaster (later known as Fort Lupton) after his Army career ended.6 By 1837 there were a total of four trading posts established along a 15 mile stretch of the South Platte River.7

Outfitting trading parties to travel directly to Indian hunting camps and villages was a common practice of the established trading posts. These mobile trading parties extended the influence of the forts, and reduced opportunities for the opposition to obtain the trade. Depending on location and terrain, the trading parties might travel via boat, pack animals, or wagons. Under the hyper-competitive trading conditions that must have existed along the South Platte, sending out mobile trading parties must have been essential for commercial survival.

The size of a mobile trading party depended in part on how far the party was to travel and with whom they were expecting to trade. A large, well-armed party was used for trade on extended expeditions or with unpredictable Indians. Richiens Lacy Wootton led an extended expedition of 14 men in the early months of 1837, while in the employ of BSVC, to trade with Sioux encampments and villages located in parts of what are now Colorado, Wyoming and Nebraska.8 On the other hand, a single experienced man accompanied by a couple of helpers was all that was necessary for a trip amongst friendly Indians. During the winter of 1846-47 “Blackfoot” John Smith, an experienced trader with the BSVC made a number of short trading expeditions to Cheyenne Indians in the vicinity of the Big Timbers located about sixty miles in the downriver direction from Bent’s Fort. On several of these expeditions, Smith took one wagon and was accompanied by Lewis Gerrard, an inexperienced seventeen year old youth, another helper by the name of Pierre, Smith’s Indian wife and two children. Only a small party was required for trade with the Cheyenne, because the Cheyenne considered BSVC traders to be family, which in a sense they were. William Bent was married to Owl Woman, a daughter of a Cheyenne chief.9

With a few exceptions records do not exist to determine what was typically taken on most of these expeditions. However, the business records of Pierre Choteau do preserve the detailed inventory of goods taken along on the outfit of James C. Robertson on December 2, 1837. Because Robertson was intending to compete directly with similar trading outfits sent out by Bent’s Fort, it is probable that the goods he carried were comparable in type and quality to those carried by the BSVC parties or those available at Bent’s Fort.

Robertson’s party likely used a wagon for transporting goods. That a wagon was available at Fort Jackson is known from the liquidation inventory of October 6, 1838. The Fort Jackson stock of trade goods was sold to BSVC by the AFC after the two companies came to a non-compete agreement. This liquidation inventory was also published by Peterson and will occasionally be referred to in the following text.10 Subsequent to the sale, Fort Jackson was completely destroyed by AFC personnel. Use of a wagon minimized the twice daily necessity of loading/unloading pack animals. Also, because handling was minimized, losses due to damage or theft were reduced as well.

The FJI trade goods are classified into thirteen functional categories which are based on those of Anderson in a similar study of French goods traded in the Western Great Lakes Region during the 1715-1760 time period.11 These functional categories are: Adornment, Clothing, Cooking & Foods, Grooming, Hunting, Weapons, Woodworking, Amusements, Digging & Cultivation, Fishing, Maintenance, Amusement, Alcohol Use and Tobacco Use. Anderson also provides a list of the types of goods that fall into each category.

Although not stated on the FJI, the prices listed are the company’s wholesale or purchase costs, not retail prices. The total inventory has a value of $935.51 which today would not appear to represent a significant trading outfit. However, adjusting for inflation from 1837 to 2010, the value of the inventory in present-day dollars is a more respectable $17,840.95.12 If these goods were sold at typical markups of approximately 1000%, sale of the entire inventory might bring in robes with a value of nearly $180,000 in present-day dollars.13

For the Great Lakes Region study, Anderson used inventories from a total of 70 outfits sent out to supply posts at Detroit, Michillimackinac, Green Bay, Oulatenon, Sioux Post, Rainy Lake, Nipigon and Michipicoten. Anderson based his inventory study on a collection of documents which he termed the Montreal Merchants Records (MMR). Anderson’s results are considered to be statistically valid because of the comprehensive size of his data set.

Specific items on the FJI have been placed in functional categories based both on Anderson’s precedent and on the generally intended use of the item. Indian consumers may well have found unique uses for these goods which are not obvious and don’t necessarily correspond to the categories to which they’ve been assigned. An example of one such unique use would be gun screws as hair ornamentation used by a Blackfoot warrior.14 Other metal items that occasionally saw use for decorative purposes include awls, knives, forks, nails, buckles, bottle labels, keys, fishhooks, saucepan handles, pocket watch parts, and instrument wheels. Six serpent side-plates from NW Trade Guns were once fashioned into a warrior’s breastplate.15 Table 1 below shows the functional categories of the FJI arranged in descending order of percent value:

Table 2 compares the ranking of the functional categories between the FJI and the statistically valid data set for the MMR:

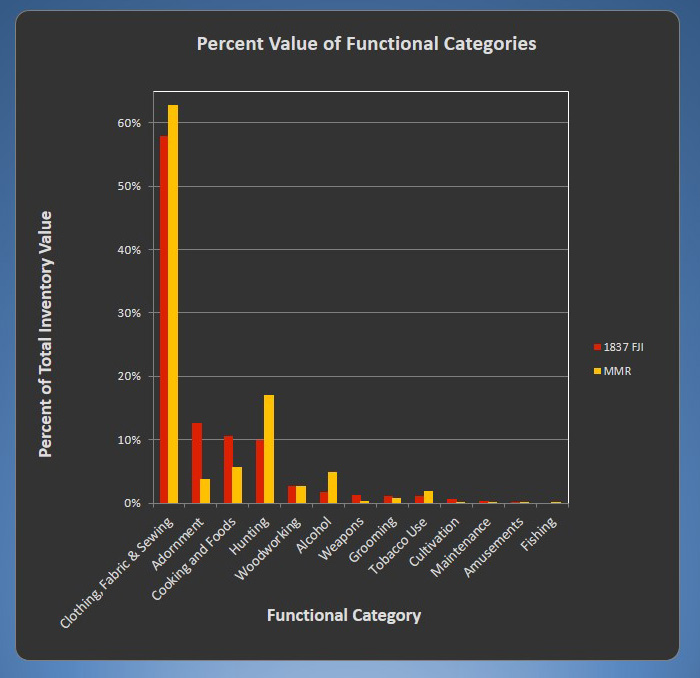

Table 2 shows that rank and percent of total inventory value of the different functional categories are remarkably similar between the FJI and MMR, especially considering differences in time (1837/1715-1760), location and culture of the consumer (plains Indians/northern woodlands Indians), life style (nomadic/semi-permanent to semi-nomadic), and predominant source of goods (American-English/French). For almost all categories the FJI rank falls within the range of ranks for the MMR. The most significant difference between the two data sets is the functional category represented by Hunting. On the MMR the Hunting category is clearly ranked 2, whereas on the FJI, Hunting is 4 behind Clothing, Adornment, and Cooking & Food. All three of these categories are very close in relative percent values on the FJI, and slightly different distribution of trade goods could easily have reversed these category rankings.

Figure 2 is a graphical representation of the relative importance of the functional categories and comparison between the 1837 FJI and the MMR inventories.

The four highest ranked functional categories, which include Clothing, Fabric and Sewing; Adornment; Cooking and Foods; and Hunting, constitute more than 90 percent of the inventory value. The remaining nine functional categories make up less than 10 percent of the inventory value.

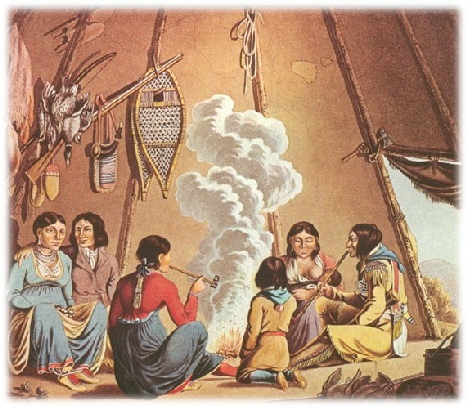

The four main functional categories for both the FJI and MMR are Clothing, Fabric & Sewing; Adornment; Cooking & Foods and Hunting. Table 1 shows the comparison of these specific functional groups. It is interesting that two of the top four categories, Clothing, Fabric & Sewing and Cooking & Foods, fall entirely within what is considered to be the domain of the Plains Indian women. Adornment was important to both men and women. Only the Hunting category falls exclusively in the domain of male responsibility. This suggests that while Indian males may have been responsible for conducting trade, the women would have had considerable input in many purchasing decisions.

Clothing, Fabric & Sewing: This functional category, which includes blankets, fabric and sewing needs, as well as ready-to-wear clothing, is the single largest functional category for both the FJI and the MMR inventories and constitutes roughly two-thirds of the inventory value of both data sets. By obtaining ready-made clothing and textiles, a woman’s workload dedicated to clothing production was significantly reduced, allowing her to reallocate her time to different tasks, including additional time for preparing and dressing furs and skins.

Blankets alone constitute nearly one-quarter of the entire inventory value and nearly half the value of this functional category. Blankets described on the inventory were available as pairs in red, green, blue and white. When first woven, a roll of blanketing material might be as long as 150 feet17, which was then cut into more manageable pairs.18 At the place of purchase the consumer then had the option of buying a single blanket, which would be cut or torn from a pair, or purchasing the un-separated pair which could be used in a manner similar to a sleeping bag.19 Most of the blankets on this inventory are 3-point blankets with lesser quantities of 2 ½, 2 and 1

point blankets. The wholesale costs of the 3-point blankets range from $6.90 to as high as $11.01 per pair.

Excluding blankets, this category is split almost evenly in value between ready-made clothing and fabrics. Ready-made clothing includes five capotes, twenty shirts, three pair of pantaloons, nine caps and hats, ten Chief’s Coats, four pair of socks, one shawl and six leather belts. The most expensive clothing items are scarlet and blue Chief’s Coats at $8.25 and $7.70 each, respectively. The Chief Coats were very expensive items and were probably intended to be distributed as gifts.

With 256 yards of various types and colors of fabrics, it is clear that trader putting

together this outfit knew Indian women to be proficient seamstresses who preferred

the fit, fashion and value obtained by sewing clothing themselves. The quantity

of fabric is sufficient for approximately 85 shirts or 85 of dresses of the style

favored by the Indian women. Other sewing items included on this inventory are one

pound of linen thread and 1½ gross gilt buttons. It is quite possible that the buttons

were for use as decorative items rather than as clothing fasteners. One item obviously

missing from the FJI, especially given the quantity of fabric, is needles. Being

very low cost items, needles and pins may have been intended as complementary items

to be given out with the purchase of fabrics and as a result were not recorded on

the inventory. The Bent’s Fort ledgers for July 24, 1839 record a cost of $2.25

per thousand needles.20 The liquidation inventory of October 6, 1838 shows that

needles were available at Fort Jackson.21

women to be proficient seamstresses who preferred

the fit, fashion and value obtained by sewing clothing themselves. The quantity

of fabric is sufficient for approximately 85 shirts or 85 of dresses of the style

favored by the Indian women. Other sewing items included on this inventory are one

pound of linen thread and 1½ gross gilt buttons. It is quite possible that the buttons

were for use as decorative items rather than as clothing fasteners. One item obviously

missing from the FJI, especially given the quantity of fabric, is needles. Being

very low cost items, needles and pins may have been intended as complementary items

to be given out with the purchase of fabrics and as a result were not recorded on

the inventory. The Bent’s Fort ledgers for July 24, 1839 record a cost of $2.25

per thousand needles.20 The liquidation inventory of October 6, 1838 shows that

needles were available at Fort Jackson.21

After Clothing, the next three highest ranking categories on the FJI are Adornment, Cooking & Foods, and Hunting. These categories are quite close to each other in value, ranging from 12.7 to 9.9 percent and constitute a cumulative total of 33.2 percent of the inventory value. With slightly different quantities or mix of goods the rankings of these three categories could easily have been reversed. On the MMR inventories Hunting is clearly second ranked at 17 percent, being more than three times the value of the next higher category, while Adornment, at 3.7 percent is ranked fifth. The differences in ranking of these functional categories may be an aberration resulting from the small size of the FJI data set. However, if the ranking of the FJI is representative of the distribution of goods traded with the plains Indians, it suggests that the Plains Indians expended relatively fewer resources and effort in meeting their food requirements than the northern woodland Indians. If this is correct, Plains Indians would have had more discretionary resources and time, and thus could place a relatively higher priority on luxury items.

Adornment: Adornment is the second ranked category on the FJI with 12.7 percent

of the inventory value. From  descriptions left by early journalists on the plains

it is clear the Plains Indians were particular about their personal appearance and

the appearance of their possessions and had the discretionary time and resources

to allocate to this category. According to F.A. Wislizenus writing about his observations

of the Kaw Indians in 1839, “Like all Indians, they are fond of painting themselves

with vermilion. A red ring around the eyes is considered particularly becoming.

To the dressing of the hair the men give more care than the women..…. Both sexes

also adorn themselves with all possible ornaments of beads, coral, brassware, feathers,

ribbons, gaudy rags, etc.”22 John Wyeth writes this description of a Blackfoot Chief

in 1833:23 “The Black-foot chief was a man of consequence in his nation. He not

only wore on this occasion a robe of scarlet cloth, probably obtained from a Christian

source, but was decorated with beads valued there at sixty dollars.” This was a

great display of wealth because at this time unskilled labor is valued at $70 or

less per year and gold at less than $20.00 per ounce.24

descriptions left by early journalists on the plains

it is clear the Plains Indians were particular about their personal appearance and

the appearance of their possessions and had the discretionary time and resources

to allocate to this category. According to F.A. Wislizenus writing about his observations

of the Kaw Indians in 1839, “Like all Indians, they are fond of painting themselves

with vermilion. A red ring around the eyes is considered particularly becoming.

To the dressing of the hair the men give more care than the women..…. Both sexes

also adorn themselves with all possible ornaments of beads, coral, brassware, feathers,

ribbons, gaudy rags, etc.”22 John Wyeth writes this description of a Blackfoot Chief

in 1833:23 “The Black-foot chief was a man of consequence in his nation. He not

only wore on this occasion a robe of scarlet cloth, probably obtained from a Christian

source, but was decorated with beads valued there at sixty dollars.” This was a

great display of wealth because at this time unskilled labor is valued at $70 or

less per year and gold at less than $20.00 per ounce.24

There are a great variety of goods in this class including various sizes of bells and beads, mirrors, combs, shells, different types of plumage, rings, vermilion, silver armbands & gorgets and brass tacks. Beads are by far the single most common item constituting more than half of the category value. The 1837 inventory does not describe bead sizes, except for 52 pounds of seed beads. Depending on the exact size of the seed beads listed on the inventory, 52 pounds might have numbered more than 2.5 million beads.

Cooking & Foods is the third ranked functional category on the FJI at 10.6 percent.

This category includes assorted knives, assorted brass, sheet iron and jappaned

kettles, bails, and fire steels. A very limited selection of  foodstuffs is represented

including coffee, sugar and rice.

foodstuffs is represented

including coffee, sugar and rice.

Knives make up more than half of the value of this category on the FJI, and kettles and pans more than 30 percent. There is a single line item for “assorted” knives, no other detail is provided, but the inventory line indicates that 23 dozen were taken at a cost of $2.28 a dozen. According to the March 1838 liquidation inventory Fort Jackson had on hand various sizes of butcher knives, finest and second quality scalping knives, green and white handled cartouche knives (which resemble modern-day steak knives), fancy, inlaid-handled knives, and single and double-bladed folding knives.25 The assorted knives on this inventory likely represented some combination of those shown on the liquidation inventory, but probably biased towards scalpers and butchers, two of the most popular types. The cost of $2.28 per dozen most likely represents an average cost of the assorted knives.

From the inventory it is obvious that the Indians had little desire for exotic food items. Foodstuffs represent less than one-eighth the value of this category. There are only three items of food on the FJI, 35 pounds of coffee, 60 pounds of sugar, and 10 pounds of rice. Some of the food items may have been intended for the traders own use.

Hunting: is the fourth highest functional category by value constituting 9.9 percent of the inventory value. In the MMR data, Hunting clearly ranks 2nd at 17.0 percent of the total value, and is more than three times the value of the next highest category. In the FJI this category is exclusively composed of guns, and shooting supplies. There is only one item which is not shooting related that might be placed in this category, 3 pounds of iron wire. Anderson places wire in the Hunting category on the MMR because it was used for constructing snares for small game. However, because traps are not included on the FJI I have conclude that small game was generally not of interest to these Indian consumers and that iron wire was more likely used for binding or fastening materials and so I have placed it in the Maintenance category.

The guns and gun supplies in this category include six long and six short fusils, 7 powder horns, 50 pounds of powder, 100 pounds of ready-made balls, 20 pounds of lead, and flints and gun worms.

Not enough information is provided with the inventory to speculate about long vs. short fusils. Most of the NW Trade Guns illustrated in Firearms of the Fur Trade for this general time period range in barrel length from 35 inches up to 42 inches with a range of calibers between .57 to .68 with most being .60 or .62.26 The wholesale cost of the guns were $4.95 and $5.10.

The inventory does not indicate whether the 100 pounds of trade balls are of a single size, or are of multiple sizes, but were probably dominated by sizes appropriate for the trade guns. The powder/lead ratio by weight of the Fort Jackson trading camp inventory is 1:2.4.27 This is almost identical to the powder/lead ratio of 1:2.5 in use by native hunters in 1760 as determined by Sir William Johnston.

Flints and gun worms are a single line item listed at $1.00. It is initially perplexing as why to such different items should be listed together with no quantities given. These were very low cost items. The Sybille, Adams & Co. manifests from 1843 show costs of approximately three-tenths cent per gunflint and six-tenths cent per gun worm.28 One possible interpretation for this line item is that a handful of flints and worms were simply grabbed and the value estimated without taking the effort to tally individual units. The flints were most likely of English manufacture as by the 1800’s most gunflints available in North America were of the dark grey or black flint and having a regular prismatic shape.29

Although the minor and trace functional categories represent less than 10 percent of the total value of the inventory, they are none-the-less significant and necessary to the inventory. Some of the items in these categories were highly profitable for the trader, other items were essential to maintain the lifestyle of the Indian consumers.

Minor functional categories are defined as those categories with percent level values of between 1 and 5 percent. Categories ranked 5 through 9 on the FJI meet this criterion and are Woodworking; Alcohol; Weapons; Grooming and Tobacco Use. These five categories have a cumulative value of approximately 8 percent and range in value from 1.1 percent up to 2.7 percent. With the exception of Alcohol, these categories compare fairly well with the MMR inventories both in terms of rank and percent value.

Woodworking: This category makes up 2.7 percent of the FJI inventory total and with a rank of 5. This is almost identical in value and rank to the MMR. There are only two items described on the FJI inventory that fall into this category; 25 squaw axes at 82¢ each, and 3 Collins axes at $1.70 each. The close comparison of this functional category between the FJI and MMR is surprising. The northern woodland Indian consumers of the MMR would have been expected to have much greater utility and need for woodworking tools than the Plains Indian consumers of the FJI.

Alcohol on the FJI ranks 6 at 1.8 percent of the inventory value. This falls within

the range of ranks on the MMR, but with a value far below the average percent value

of 4.84 percent on the MMR inventories. Fifteen gallons of alcohol was taken on

the December1837 trading venture with a wholesale price of $1.10 per gallon. Although

this category represents less than two percent of the total inventory value, if sold,

the profits were likely immense. In 1841 David Adams was charging customers at his

post on the North Platte the equivalent of $32.00 per gallon for undiluted alcohol.30

If James Robertson was selling undiluted alcohol for similar prices, the markup would

have been greater than 3,000 percent. However, it is quite likely that some of this

alcohol was intended to be given out with other gifts to the Indians as part of the

necessary rituals establishing friendship and goodwill prior to opening trade. In

December 1846 Lewis Garrard describes arriving in an Indian village which was in

an uproar because “opposition traders” had conferred a gift of liquor.31 Whether

to be gifted or traded, it is almost certain that the alcohol was diluted substantially

prior distribution to the Indian consumers.

1841 David Adams was charging customers at his

post on the North Platte the equivalent of $32.00 per gallon for undiluted alcohol.30

If James Robertson was selling undiluted alcohol for similar prices, the markup would

have been greater than 3,000 percent. However, it is quite likely that some of this

alcohol was intended to be given out with other gifts to the Indians as part of the

necessary rituals establishing friendship and goodwill prior to opening trade. In

December 1846 Lewis Garrard describes arriving in an Indian village which was in

an uproar because “opposition traders” had conferred a gift of liquor.31 Whether

to be gifted or traded, it is almost certain that the alcohol was diluted substantially

prior distribution to the Indian consumers.

There is no indication in the inventory as to the origin of the alcohol. Most trade goods at Fort Jackson were probably received by way of Fort Laramie, the American Fur Company’s (AFC) primary trading center in the region. However, the company had good reason to be hesitant about transporting it’s alcohol via this route in 1837. In 1832 the U.S. Congress placed a total ban on the introduction of ardent spirits into Indian country.32 In order to evade this restriction in 1833 Kenneth McKenzie imported a still to Fort Union (AFC). It wasn’t long before opposition traders tipped off the federal authorities. During the ensuing brouhaha in 1833-34 the company was severely embarrassed, had to call in considerable political favors and was in some danger of losing its license to trade in the Indian country.33 It would be reasonable to guess that the alcohol on the 1837 inventory was obtained from one of the many distilleries in the Taos valley, quite possibly one operated by Simeon Turley, an American expatriate living in Mexico at that time. The shipping distance from Taos to Fort Jackson was just over three hundred miles, approximately half the distance from Independence, Missouri. Furthermore, if this alcohol was produced by Simeon Turley, delivery may have even been included as part of the transaction. By 1836 competition in the Taos area between whiskey distillers had become so intense that Turley hired Charles Autobees to act as a salesman, exchanging whiskey and coarse Mexican flour for robes at American trading posts on the South and North Platte Rivers.34 That commercial transactions between Autobees and Fort Jackson took place is revealed by a document showing that Sarpy and Fraeb paid “Charles Ottabees” $13 on March 1, 1838, though the document apparently does not specify what was being sold or exchanged.35 Alcohol from the Taos distillers therefore not only had the advantage of lower transportation costs, but was virtually free from the risk of confiscation or political embarrassment as well. Lower transportation costs might also partially explain the differences in percent value and rank of this category between the FJI and MMR.

Weapons rank 7 on the on the FJI with a value of 1.3 percent of the total inventory. This category is slightly higher both in rank and percent value than the same MMR category. The category is composed of five battle axes at $1.92 ½ each and one small sword at $2.25.

The small sword is likely a novelty item or curiosity, but whether this was included in the inventory as part of a special order, or simply as a test of consumer interest cannot be determined.

Precisely what a battle axe is I have not been able to determine. They are not pipe tomahawks, because these two items are listed separately on Bent’s Fort ledgers36 with battle axes priced at $1.75 (which is nearly equivalent to the price of the Fort Jackson battle axes), and pipe tomahawks priced at $3.00.

Grooming ranks 8 on the FJI with 1.1 percent of the total value. This category has the same rank as the average MMR, though a slightly higher percent value. The category is composed of five dozen of various types of looking glasses and 8 dozen combs. Although there are a large number of individual pieces in this category, all of the items are relatively inexpensive.

Tobacco: This category ranks 9 on the FJI with 1.1 percent of the inventory value. The percent value of this category is roughly comparable to the MMR inventories although on the MMR inventories it has an average rank of 7. According to the FJI, 90 pounds of what appears to be a single grade of tobacco was taken. Almost certainly some portion of the tobacco was intended for use as gifts to establish good will and friendship with the Indian customers. The remaining tobacco would have been highly profitable as a trade item. In 1841 David Adams was charging customers at his post on the North Platte $1.50 per pound (approximately a 1200% markup over his wholesale cost) for what appears to be a similar grade of tobacco.37 An item conspicuous by its absence from the FJI inventory list is clay tobacco pipes, especially given the quantity of tobacco taken. The October 1838 liquidation inventory shows that Fort Jackson had a considerable supply of tobacco pipes at that time, listing 350 pipes plus additional cases of uncounted pipes. Clay pipes were another very inexpensive item. The Fontenelle, Drips & UMO inventory for 1833 lists clay pipes at 68¢ per gross, that is less than ½ cent each.38 As with needles and fabric discussed in Part II, I suspect that pipes were intended to be given out as complementary items along with the purchase of tobacco.

Trace functional categories are defined as those categories with values of less than one percent. Categories ranked 10 through 12 on the FJI meet this criterion and are Cultivation; Maintenance; and Amusements. The 13th ranked category on the MMR inventories, Fishing, is totally lacking on the FJI although fish-hooks were available at Fort Jackson as listed on the 1838 liquidation inventory.39 These categories represent a cumulative total value of less than 1 percent of the FJI.

Cultivation: There is only one item related to cultivation on the FJI, fifteen common hoes. This is an interesting item, because if used for its intended purpose, its presence suggests that the Plains Indian consumers, who were largely nomadic, practiced at least some limited forms of agriculture. The hoes may have been used to start gardens in sheltered locations which were then left to survive as best they could until the village returned to that location later in the summer or fall. John R. Bell notes in his journal several such untended gardens of corn, pumpkins and watermelons at locations along the Arkansas River in 1820.40

Maintenance: A total of sixteen assorted files and three pounds of iron wire represent this category on the FJI. The files would have found use for sharpening knives and axes and they would have also been suitable for shaping wood, bone and soft stone into useful or decorative shapes.

Amusements: Nine packs of playing card constitute the entirety of this category.

Gambling was a favorite activity amongst the Indians and with the introduction of

playing cards, card games were quickly adapted by the Indians for that purpose41

though with some variations on traditional card games. For example, soldiers at Fort

Pierre in 1855 attempted to teach the Indians Poker.42 Due to cultural differences

these attempts produced an unusual deviation of the rules. The Indians esteemed the

Jacks and dubbed them "Chiefs" valuing them over the Kings. They also considered

the Queens to be equivalent to a squaw, which therefor was valued less then a deuce.

amongst the Indians and with the introduction of

playing cards, card games were quickly adapted by the Indians for that purpose41

though with some variations on traditional card games. For example, soldiers at Fort

Pierre in 1855 attempted to teach the Indians Poker.42 Due to cultural differences

these attempts produced an unusual deviation of the rules. The Indians esteemed the

Jacks and dubbed them "Chiefs" valuing them over the Kings. They also considered

the Queens to be equivalent to a squaw, which therefor was valued less then a deuce.

Summary: Although the data set represented by the FJI is statistically insignificant, it compares remarkably well with the MMR. This suggests that the ranking of functional categories on the FJI is probably not significantly skewed by one-time factors and likely is representative of the types and distribution of trade goods taken by other trading camps to plains Indians. Because the Fort Jackson trading party might have been competing directly with other trading parties (sent out by the Bent, St. Vrain & Co., as well as other independent traders) the distribution of types of goods is likely representative of these trading parties as well. The rough transposition of Adornment and Hunting functional categories is the most significant difference between the FJI and MMR suggesting that the Plains Indians expended relatively fewer resources in food production than the northern woodland Indians. This resulted in greater leisure time and surplus resources that could be diverted to discretionary items in Adornment category. This seemingly correlates with the physical environment in which these Indians existed in. The Plains Indians typically would take large numbers of buffalo by horseback from the immense herds of these animals that roamed the prairies, whereas Indians in the northern woodlands would have hunted large game animals singlely, including deer, bear, elk, moose and buffalo as well as small game.

The December 2nd, 1837 inventory offers a significant view into the needs and desires of the Plains Indian consumer. Foremost, the Indian consumer was most interested in fashionable, comfortable, colorful clothing, and soft, warm, woolen blankets. Next the Indian consumer was interested in items which could be used to improve his or her attractiveness, make their environment more pleasurable, and to decorate or beautify objects in and around their dwellings. Items for cooking, hunting, as well as adornment are all important, and cumulatively constitute a third of the inventory. The remaining categories, which include Woodworking, Alcohol, Weapons, Grooming, Tobacco, Cultivation, Maintenance, and Amusements, represent a relatively minor though important part of the inventory, with all of these classes totaling less than ten percent of the total value. Contrary to common perceptions, this trading outfit in no way resembled either a mobile tavern/liquor store or weapons shop, but was far more comparable in variety and types of goods to those stocked by a modern department store.

1Guy L. Peterson, Four Forts of the South Platte (n.p., Council on America’s Military Past, 1982), 55.

2Dean L. Anderson, The Flow of European Trade Goods into the Western Great Lakes Region, 1715, in The Fur Trade Revisited: Selected Papers of the Sixth North American Fur Trade Conference, Mackinac Island, Michigan, 1991, edited by Jennifer S.H.Brown, W.J. Eccles and Donald P. Heldman, Lansing Michigan, Michigan State University Press, 93-115.

3Peter J. Powell, People of the Sacred Mountain: A history of the Northern Cheyenne Chiefs and Warrior Societies, 1830-1879, Vol. 2, (New York, Harper and Row, 1981) 728; Peterson, 52.

4Peterson, 7.

5Rufus Sage, Rocky Mountain Life, or Startling Scenesand Perilous Adventures in the Far West (Edward Canby publisher, Dayton Ohio, no publication date given), 212.

6Paul Chrisler Phillips, The Fur Trade (Norman, Oklahoma, University of Oklahoma Press, 1961) 539-543.

7Ibid., 428; The Western Department of the American Fur Company was sold in early 1834 to Pratte, Choteau and Company following the retirement of John Jacob Astor. However, even after the change in ownership the successor company continued to be generally known as the American Fur Company.

8Richiens Wootton, as told to Howard Louis Conrad, Uncle Dick Wootton: The Pioneer Frontiersman of the Rocky Mountains (Santa Barbara, California, The Narrative Press, 2001 printing), 26-29.

9Lewis H. Garrard, Wah-To-Yah and the Taos Trail, Oklahoma City, Harlow Publishing Co., 1927), 44-47.

10Peterson, 56-62.

11Anderson, 93-115.

12“The Inflation Calculator,” http://www.westegg.com/inflation.cgi [accessed February 28, 2012].

The markup is a rough value determined by the author’s unpublished research of accounts of Sybil and Adams published in The David Adams Journal, ed. 13Charles E Hanson, Jr., (Chadron, Nebraska, Museum of the Fur Trade, 1994).

14Frances Fuller Victor, The River of the West: Life and Adventure in the Rocky Mountains and Oregon, Volume I edited by Winfred Blevins (Missoula, Montana, Mountain Press Publishing Co. 1983), 230.

15Karlis Karklins, Trade Ornament Usage Among the Native Peoples of Canada: A Source Book (Ottawa, published by the Minister of the Environment, 1992), 110, 228.

16“The Point Blanket Site,” http://www.pointblankets.com/pages/pb003.htm [accessed January 8, 2012] size and weights will be approximate; Robert C. Wheeler, A Toast to the Fur Trade: A Picture Essay on Its Material Culture, (St. Paul, Minnesota, Wheeler Productions, 1985), 62; Ryan R. Gale, The Great Northwest Fur Trade: A Material Culture, 1763-1850 (Elk River, Minnesota, Track of the Wolf, Inc., 2009), 38.

17Harold Tichenor, The Blanket: An Illustrated History of the Hudson’s Bay Point Blanket (n.p., published by Quantum Books for Hudson’s Bay Company, 2002), 29.

18IBID, 32.

19IBID, 12.

20Ledger DD, April 16, 1839-July 1840, Pierre Chouteau Collection, Missouri Historical Society, St Louis, pp 76-89.

21Peterson, 56-62.

22Frederick Adolph Wislizenus, A Journey to the Rocky Mountains in the Year 1839 (St Louis, Missouri Historical Society), 33.

23John Wyeth, Oregon; or A Short History of a Long Journey from the Atlantic Ocean to the Region of the Pacific by Land, 1833, http://user.xmission.com/~drudy/mtman/html/jwyeth.html [accessed May 30, 2012]

24“Historical Gold Prices: 1833 to Present,” http://www.nma.org/pdf/gold/his_gold_prices.pdf [accessed December 14, 2012]

25Peterson, 57-62.

26James A. Hanson with Dick Harmon, Firearms of the Fur Trade, Encyclopedia of Trade Goods, Volume 1, (Chadron, Nebraska, Museum of the Fur Trade, 2011),, 324-347.

27Walter S. Dunn, Jr., The New Imperial Economy: The British Army and the American Frontier, 1764-1768. (Westport, Connecticut, Praeger Publishers, 2001), 97.

28David Adams, The David Adams Journal, ed. Charles E Hanson, Jr., (Chadron, Nebraska, Museum of the Fur Trade, 1994), 51.

29George Irwing Quimby, Indian Culture and European Trade Goods (Madison, Milwaukee, London, The University of Wisconsin Press, 1966), 75; Sydney B.J. Skertchly, On the manufacture of Gun-Flints, The Methods of Excavating for Flint, The Age of Palæolithic Man, and The Connexion Between Neolithic Art and the Gun-Flint Trade (London, Published by Order of the Lords Commissioners of Her Majesty’s Treasury, 1879) 46-64.

30David Adams, The David Adams Journal, ed. Charles E Hanson, Jr., (Chadron, Nebraska: Museum of the Fur Trade, 1994), 14.

31Lewis H. Garrard, Wah-To-Yah and the Taos Trail, (Oklahoma City: Harlow Publishing Co., 1927), 76.

32Barton H. Barbour, Fort Union and the Upper Missouri Fur Trade (Norman Oklahoma: University of Oklahoma Press, 2001), 151.

33Paul Chrisler Phillips, The Fur Trade (Norman, Oklahoma: University of Oklahoma Press, 1961), 426-429.

34Janet Lecompte, Simeon Turley, in The Mountain Men and the Fur Trade of the Far West, Vol. VII, ed. LeRoy Hafen (Spokane, Washington: Arthur H Clark Co. 2003), 304.

35Janet Lecompte, Charles Autobees, in The Mountain Men and the Fur Trade of the Far West, Vol. I, ed. LeRoy Hafen (Spokane, Washington: Arthur H Clark Co. 2003), 33.

36Ledger Z, May, 1838-July, 1839, Pierre Chouteau Collection, Missouri Historical Society, St. Louis pp 426-433, and Ledger DD, April 16, 1839-July 1840, Pierre Chouteau Collection, Missouri Historical Society, St Louis, pp 76-89.

37Adams, 4-15.

38Fontenelle, Drips and U.M.O. June 1, 1833 accounts, Pratte, Chouteau & Co., Vol. EE, page 6, Choteau-Maffitt Collection of the Missouri Historical Society, St. Louis, Fur Trade Ledgers.

39Peterson, 56-62.

40John R. Bell, The Journal of Captain John R. Bell: Official Journalist for the Stephen H. Long Expedition to the Rocky Mountains, 1820, edited by Harlin M. Fuller and LeRoy R Hafen (Glendale, California: The Arthur H. Clark Company, 1957) 230, 236.

41Caleb Atwater, Tour to Prairie du Chien; Then to Washington City in 1829 (Columbus, Ohio: Isaac N. Whiting, 1831), 117.

42Robert G. Athearn, Forts of the Upper Missouri, (n.p.: Prentice Hall, Inc. 1967), 45.

|

Table 1: Functional Category Values of the Fort Jackson Inventory | ||

|

Category |

Wholesale $ Amount |

Percent of Total |

|

Clothing, Fabric & Sewing |

$541.42 |

57.9% |

|

Adornment |

$118.61 |

12.7% |

|

Cooking & Foods |

$98.96 |

10.6% |

|

Hunting |

$92.98 |

9.9% |

|

Woodworking |

$25.60 |

2.7% |

|

Alcohol |

$16.50 |

1.8% |

|

Weapons |

$11.87 |

1.3% |

|

Grooming |

$10.12 |

1.1% |

|

Tobacco & Tobacco Use |

$9.90 |

1.1% |

|

Cultivation |

$5.44 |

0.6% |

|

Maintenance |

$2.77 |

0.3% |

|

Amusements |

$1.35 |

0.1% |

|

Fishing |

NA |

NA |

|

Table 2: Comparison of Functional Categories | ||||||

|

|

1837 Fort Jackson Inventory |

|

Montreal Merchant Records Inventories | |||

|

Category |

% of Total |

Rank |

|

Ave. Rank |

Range of Rank |

Ave % of Total |

|

Clothing, Fabric & Sewing |

57.9% |

1 |

|

1 |

1 |

62.85% |

|

Adornment |

12.7% |

2 |

|

5 |

3-7 |

3.73% |

|

Cooking & Foods |

10.6% |

3 |

|

3 |

3-5 |

5.65% |

|

Hunting |

9.9% |

4 |

|

2 |

2 |

17.00% |

|

Woodworking |

2.7% |

5 |

|

6 |

4-8 |

2.71% |

|

Alcohol |

1.8% |

6 |

|

4 |

3-6 |

4.84% |

|

Weapons |

1.3% |

7 |

|

9 |

7-12 |

0.32% |

|

Grooming |

1.1% |

8 |

|

8 |

6-10 |

0.75% |

|

Tobacco & Tobacco Use |

1.1% |

9 |

|

7 |

6-8 |

1.84% |

|

Cultivation |

0.6% |

10 |

|

10 |

9-11 |

0.05% |

|

Maintenance |

0.3% |

11 |

|

11 |

10-13 |

0.06% |

|

Amusements |

0.0% |

12 |

|

13 |

10-13 |

0.01% |

|

Fishing |

Absent |

13 |

|

12 |

10-13 |

0.05% |

|

Table 3: Comparison of the Four Main Functional Categories | ||||||

|

|

1837 Fort Jackson Inventories |

|

Montreal Merchants Records Inventories | |||

|

Category |

% of Total |

Rank |

|

Ave. Rank |

Range of Rank |

% of Total |

|

Clothing, Fabric & Sewing |

57.9% |

1 |

|

1 |

1 |

62.85% |

|

Adornment |

12.7% |

2 |

|

5 |

3-7 |

3.73% |

|

Cooking & Foods |

10.6% |

2 |

|

3 |

3-5 |

5.65% |

|

Hunting |

9.9% |

4 |

|

2 |

2 |

17.00% |

|

Point Blankets- Size & Weights16 | ||

|

Points |

Size (Inches) |

Weight |

|

3 1/2 |

63X81 |

5 lbs |

|

3 |

62X72 |

4 lbs |

|

2 1/2 |

50X66 |

3 lbs 6 oz |

|

2 |

42X58 |

2 lbs 3.5 oz |

|

1 1/2 |

36X51 |

1 lbs 12.5 oz |

|

1 |

32X46 |

1 lbs 8.5 oz |

|

Table 4. Comparison of Minor and Trace Functional Categories | ||||||

|

|

1837 Fort Jackson Inventory |

|

Montreal Merchant Records Inventories | |||

|

Category |

% of Total |

Rank |

|

Rank |

Range of Rank |

Ave % of Total |

|

Woodworking |

2.70% |

5 |

|

6 |

4-8 |

2.71% |

|

Alcohol |

1.80% |

6 |

|

4 |

3-6 |

4.84% |

|

Weapons |

1.30% |

7 |

|

9 |

7-12 |

0.32% |

|

Grooming |

1.10% |

8 |

|

8 |

6-10 |

0.75% |

|

Tobacco Use |

1.10% |

9 |

|

7 |

6-8 |

1.84% |

|

Cultivation |

0.60% |

10 |

|

10 |

9-11 |

0.05% |

|

Maintenance |

0.20% |

11 |

|

11 |

10-13 |

0.06% |

|

Amusements |

0.10% |

12 |

|

13 |

10-13 |

0.01% |

|

Fishing |

Absent |

13 |

|

12 |

10-13 |

0.05% |

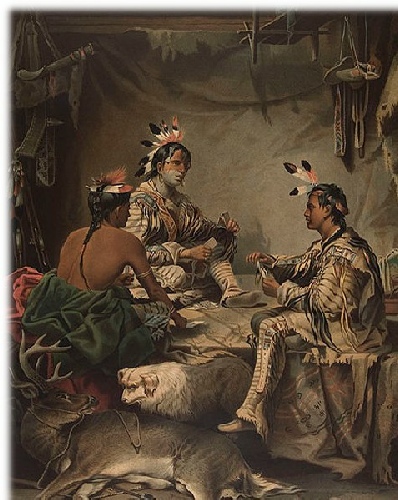

Seth Eastman 1851

Karl Bodmer 1833

Seth Eastman “Good Medicen” 1840’s

John Mix Stanley 1867